KING OF BAD TIMES: Corporate honcho Vijay Mallya has fallen on bad times with the banks selling his property, including the Kingfisher Villa in Candolim, Goa, and issuing a warrant for his extradition from the UK for prosecution for fraud

By Rajan Narayan

WHAT will the banks do with all the money they forced us to deposit under the excuse of fighting black money? Exactly what they have been doing all the time.

They will lend your and my hard-earned money to big business houses like Vijay Mallya’s Kingfisher and Subrata Roy’s Sahara Group, who among other big businessmen have swindled our banks, particularly the nationalised banks, of thousands of crores. Mallya is having a gala time in London after diverting the `7,000 crore that he borrowed from banks to buy race horses and yachts instead of planes for the Kingfisher airlines he started with public money. The Sahara chief on the other hand is alleged to have cheated small depositors of more than `30,000 crore.

The Public Finance Public Accountability Collective has revealed that it is big industrial houses like Adani, Essar, GMR (Grandhi Mallikarjuna Rao), GVK (Gunupati Venkata Krishna), JSW, JPA, Lanco, Reliance, ADA, Vedanta and Videocon who have been the beneficiaries of 13 per cent of the total bank loans and 98 per cent of the net worth of the banking system. Each of these groups alone now account for two per cent of the total loans of the public sector banks.

There is every risk that the huge loans taken by these companies running into thousands of crores will turn into non-performing assets. This means dead assets which cannot produce any goods or generate adequate income to repay even interest, let alone principle.

When you and I apply for a personal loan to the bank to buy a two-wheeler or a 1 BKH the bank will demand all kinds of sureties. It will insist that the two wheeler or the 1 BHK be mortgaged to the bank so it can take them away if you do not pay an Equated Monthly Instalment (EMI) on time. If you default on your instalments the banks will even send goons to your house to recover the two-wheeler or the 1 BHK.

But when it comes to crorepatis, banks are very reluctant to demand adequate security. It does not occur to them that rich people like Vijay Mallya or Ramalingam Raju of Satyam, will cheat them.

But when it comes to crorepatis, banks are very reluctant to demand adequate security. It does not occur to them that rich people like Vijay Mallya or Ramalingam Raju of Satyam, will cheat them.

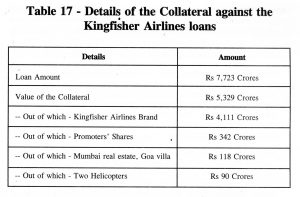

The consortium of banks which lent more than `7,000 crore to Mallya extended a large part of the loan purely on his personal guarantee. The value of the security offered was over estimated at `5,329 crore against the loan amount of `7,723 crore. Of these securities, the principle asset pledged was the Kingfisher brand valued by the banks at `4,111 crore, and which is now worth `0.

The central and state government need to identify and punish bankers who in collusion with politicians lent huge amounts of money to their industrialist friends. The most notorious case we can think of in Goa itself, is the then union law minister Deve Gowda who in his position as the de facto chairman of the Mapusa Urban Bank lent `25 crore to the prime minister’s son merely on the basis of a letter, without any surety or the address of the borrowers!

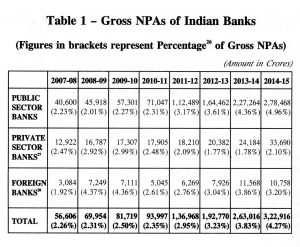

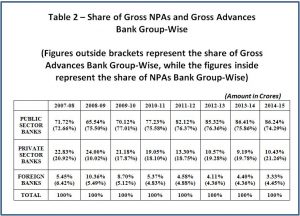

While there is no specific data released by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) or the banks on the percentage of NPAs due to loans given specifically to corporate houses, many industry experts have alleged a rise in NPAs of Indian banks has taken place over the past few years due to indiscriminate lending to companies with poor financial records and loans for risky projects. The contribution of corporate loans leading to steady rise in NPAs cannot be analysed without taking into consideration the enormous rise in corporate debt of Indian companies over the past few years, especially the concentration of debt in BSE 500 companies.

A report from May 2015 by financial services firm Standard Chartered, mentions that the total debt of BSE 500 companies grew at a compounded rate of 20 per cent from 2008-09 to 2014-15, whereas profit grew only at nine per cent in the period. Moreover, the gross debt of the BSE 500 companies rose to `24.3 lakh crore in FY 2013-14, more than 10 times the levels of `2.3 lakh crore in FY 2013-14!

Similarly, another report published in March 2015 by credit rating agency Standard & Poor’s titled ‘India’s Credit Spotlight’ mentioned that the total debt of India’s top 100 companies (except subsidiaries of multinational corporations) on the basis of market capitalisation stood at `10.5 lakh crore in the year ending March 2011, from where it has grown steadily to `13 lakh crore in the year ending March 2012 to `15 lakh crore in the year ending March 2013, and to `18.5 lakh crore in the year endingMarch 2014.

House of Debt

ANOTHER report published by financial research firm Credit Suisse in August 2012 titled ‘House of Debt’, mentions: “Over the past five years, Indian banks have witnessed strong (20 per cent CARG) loan growth. However, this growth is increasingly being driven by a select few corporate groups. In FY12, more than 20 per cent of the incremental loans came from just 10 groups.

The total debt level of these 10 (Adani, Essar, GMR, GVK, JSW, JPA, Lanco, Reliance, ADA, Vedanta and Videocon) has jumped five times in the past five years (40 per cent CAGR) and now equates to 13 per cent of the total bank loans and 98 per cent of the net worth of the banking system. Each of these groups alone now accounts (sic) for 1-2 per cent of total banking system loans.

Therefore, now in terms of the concentration risk to the top groups or to the top borrowers, Indian banks rank high compared with most of their Asian and BRIC counterparts.

High Exposure

MOREOVER, we believe the concentration risk is high as: (1) all banks appear to have high exposure to the same few groups; and (2) investments of most of these groups are in similar sectors and projects (primarily, power and metals) and many of them may be stressed. The asset profile of many of these groups is similar, with infra, and to a large extent, power assets driving up investments in the past few years.

The increase in the levels of corporate debt is not a healthy sign for any economy and can also pose a risk to the macroeconomic stability of a country, if the problem of bad loans multiples suddenly. IMF in its report ‘Regional Economic Outlook (Asia and Pacific)’ published in April 2014 raises concerns about concentration of debt in only a few, highly leveraged firms. The distribution of leverage does matter and Asia clearly has “pockets” of highly leveraged firms –including in China, Japan, India, and Korea – that may pose a risk to macroeconomic stability.

Similar concerns were echoed by the RBI in its ‘Financial Stability Report’ published in June 2015. The RBI data on sectoral credit deployment for March 2015 mentioned that out of the total non-food bank credit of `60.03 lakh crore, loans given to large industries were `21.51 lakh crore, i.e, roughly 36 per cent of the entire bank loans. The loans extended just to the power sector alone, s tood at a staggering 9.07 per cent of the loans given by entire banking industry.

tood at a staggering 9.07 per cent of the loans given by entire banking industry.

Over the past few years, banks have rapidly expanded their credit portfolio, especially by lending heavily in the infrastructure sector in hopes of a steady growth of the Indian economy. This has also increased the risk of a rise in NPAs because of an increased exposure in similar sectors, along with extending huge loans to companies concentrated in the same sector.

It is worth having a look at how the loans to large industries have grown over the past few years vis-à-vis the loans extended to micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs).

It is to be noted that over the past few years the percentage of loans given to MSMEs has declined and the percentage of loans given to large industries has steadily increased. The data provided by the RBI gives insights into the loans given across various industries, but there is less data available on which sector contributes to what percentage of NPAs.

WHERE IS THE COLLATERAL?

IN A layperson’s understanding, whenever someone takes a loan from the bank, it asks for the some ‘security’ known as collateral, which the bank may use to recover the loan if the borrower defaults.

The higher the amount of the loan, the higher the value of the collateral pledged. For example, when an individual takes a loan, one many give a house or other immovable property, such as a piece of land, as collateral.

When companies take loans from banks, it is normally assumed that they are required to pledge ‘immovable’ fixed assets or some personal property of the owners/promoters of the company. While this collateral does not automatically reduce the risk for the bank of a borrower defaulting on the loan, it acts as a major safety net for the banks.

The problem of bad loans gets worse when the banks compromise with this safety net and give loans to companies against ‘virtual assets’, like shares pledged by promoters, shares of subsidiary companies, brand names of companies, etc, which may turn out be of meagre value when the company trades at the very low value.

This became quite evident in the case of Kingfisher Airlines, where a loan of `7,723 crore was given by a consortium of banks, against the collateral amount of `5,329 crore, out of which the Kingfisher Airlines brand was alone valued at `4,111 crore.

Banks are still having a hard time recovering their money, despite dragging Mallya to court to make him pay back the loans.

The Kingfisher story may not be an isolated case of handing out loans based on poor collateral. Banks usually are very secretive about their loan deals and people are not aware of the collateral or guarantees when extending loans worth thousands of crores. When the companies default on their loans, it is the banks and the people who suffer and not necessarily the promoters of such companies.

The increasing trend of group companies/subsidiary companies acting as guarantors for many loan deals also makes the situation more precarious for banks when the guarantors do not comply in case of loan defaults.

In a move to expand their businesses rapidly, many companies have relied on the medium of roping in corporate guarantors to avail loans from the banks. However, with the increasing instances of wilful defaults, the role of guarantors needs to be spelled out more clearly in such circumstances.

In a move to expand their businesses rapidly, many companies have relied on the medium of roping in corporate guarantors to avail loans from the banks. However, with the increasing instances of wilful defaults, the role of guarantors needs to be spelled out more clearly in such circumstances.

The RBI in its ‘Master Circular on Wilful Defaulters’ dated July 01, 2015 mentions: ”While dealing with wilful default of a single borrowing company in a group, the banks/FIs should consider the track record of the individual company, with reference to its repayment performance to its lenders. However, in case where guarantees furnished by the companies within the group on behalf of the wilfully defaulting units are not honoured when invoked by the banks/FIs, such group companies should also be reckoned as wilful defaulters.”

In connection with the guarantors, in terms of Section 128 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, the liability of the surety is co-extensive with that of a principal debtor unless it is otherwise provided by the principal debtor. The banker will be able to proceed against the guarantor/ surety even without exhausting the remedies against the principal debtor.

As such, where a banker has made a claim on the guarantor on account of the default made by the principal debtor, the liability of the guarantor is immediate. In case the guarantor refuses to comply with the demand made by the creditor/banker, despite having sufficient means to make payment of the dues, the guarantor would also be treated as a wilful defaulter.

Group Guarantee

THIS treatment of non-group corporate and individual guarantors was made applicable from September 9, 2014 and not in cases where guarantees were taken before this date. Banks/FIs must ensure that this position is made known to all guarantors when accepting guarantors.

THIS treatment of non-group corporate and individual guarantors was made applicable from September 9, 2014 and not in cases where guarantees were taken before this date. Banks/FIs must ensure that this position is made known to all guarantors when accepting guarantors.

Apart from the hassles of dealing with non-compliance of guarantors in the cases of loan defaults, the trend of pledging of shares by the promoters of companies has been adding to the woes of the banks. Many listed companies in financial trouble have been pledging their shares for taking more loans from the banks.

This trend raises serious questions on the soundness of the rationale behind pledging, as share prices of companies can be highly volatile. When the pledged shares of a company perform poorly, then in case of recovery of loans, these shares would fetch very little money for banks, along with jeopardising the interest of the minority shareholders in the company.

Even the RBI has raised concerns about the issue of pledging of promoters’ shares as a means of providing collateral for taking loans. The RBI in its Financial Stability Report published in December 2014 mentions: “A majority of Indian companies are family owned/controlled, as substantial levels of promoter shareholding are concentrated within the family hold. Promoter shares can be significant collateral for a typical company if it wants to expand leverage. Pledging shares is practised in other advanced economics too, but it has taken a significantly different form in India. In the case of a typical Indian company, the promoters pledge shares not for funding ‘outside’ business ventures but for the company itself. By pledging shares, the promoters have no personal liability other than to the extent of their pledged shares. In some instances the shares pledged by unscrupulous promoters could go down in value and the promoters may not mind losing control of the company as there is a possibility of diversion of funds before the share prices collapse.”

Even the RBI has raised concerns about the issue of pledging of promoters’ shares as a means of providing collateral for taking loans. The RBI in its Financial Stability Report published in December 2014 mentions: “A majority of Indian companies are family owned/controlled, as substantial levels of promoter shareholding are concentrated within the family hold. Promoter shares can be significant collateral for a typical company if it wants to expand leverage. Pledging shares is practised in other advanced economics too, but it has taken a significantly different form in India. In the case of a typical Indian company, the promoters pledge shares not for funding ‘outside’ business ventures but for the company itself. By pledging shares, the promoters have no personal liability other than to the extent of their pledged shares. In some instances the shares pledged by unscrupulous promoters could go down in value and the promoters may not mind losing control of the company as there is a possibility of diversion of funds before the share prices collapse.”

Online financial newspaper livemint carried a story in July 2015, where it mentioned that promoters of 41 BSE-listed firms had pledged all of their shares as collateral, along with 82 company promoters pledging 90 per cent of their shares and promoters of 359 companies pledging more than half their shares.

Poor Supervision

WHILE public sector banks might be blamed for not ensuring sufficient collateral while extending loans, the banks argue that they are following the guidelines laid out by the RBI, which as a regulatory body has not specified what percentage of the collateral taken against any specific loan deal, should comprise fixed assets and what portion can be a virtual asset.

Moreover, whenever corporate loan deals are above a certain amount, banks should disclose the data in the public domain explaining the grounds on which the loan has been sanctioned and what kind of collateral banks have taken to ensure fair recovery of loans.

In order to bring transparency in the loan sanctioning process, it should be mandatory for banks to publicly disclose specific details about sanctioned loan above a certain amount (say `100 crores) to companies, such as:

- Details of the borrower

- Details of the lenders (applicable in case of consortium banking model)

- Details and type of the loan

- Amount of the loan approved

- Grounds on which loans are approved

- Conditionalities attached to the loan

- Financial track record of the company applying for loan from the banks

- Collateral taken by the banks for approving the loan

- Terms of repayment

Banks should obligatorily disclose information of large debts that are restricted, as in the case of corporate debt restructuring, lest such a mechanism should only result in ever-greening bad loans rather than assist companies overcome a difficult phase.

Excerpts from Unfolding Crisis, The Case of Rising NPAs and Sinking Public Accountability by the Public Finance Public Accountability Collective (PFPAC)