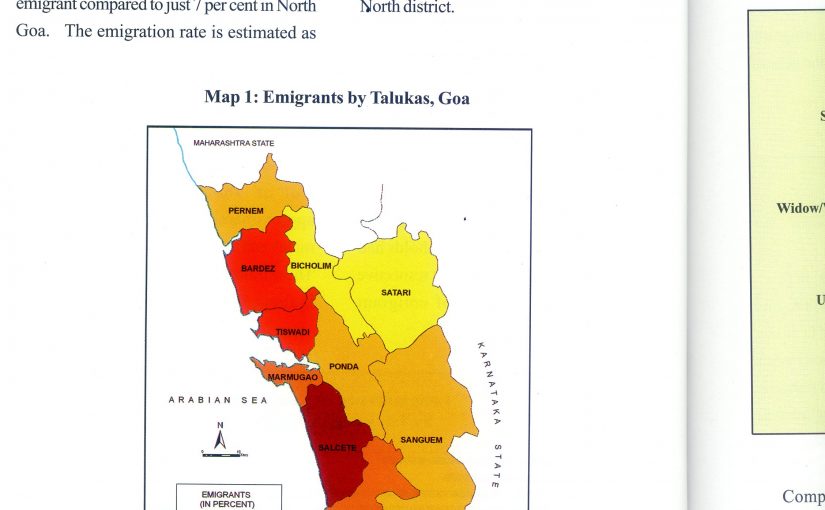

UNEQUAL: The immigration rate in South Goa is almost twice that of North Goa. Salcete itself accounts for 51 per cent of immigrant households. Bardez and Tiswadi account for 15 per cent each. Hence these three talukas alone account for 81 per cent of emigrant households. The GMS did not find even one emigrant household among the 200 sampled in Satari taluka

Most Gulf countries do not offer citizenship to migrants. The migrant’s families therefore have to be left at home. Even the US has tightened norms for work visas for wives. The study commissioned by the NRI Commision highlights the problems that families of migrants face when the main bread winner is either abroad or onboard a ship

By GO Staff

EMIGRATION brings economic benefits to the families left behind. To assess the impact on women, the Goa Migration Survey (GMS) conducted a special survey among 282 married women left behind in order to assess social and psychological stress they experience in terms of adjusting to life in the absence of their husbands. Similarly another special survey among 1,756 elderly persons (962 males and 794 females) above 60 years was conducted to understand the effect on elderly persons in the absence of their married and unmarried children who have migrated.

IMPACT ON WOMEN

THE number of women left behind in Goa due to the husband’s emigrations was estimated at 17,873. For every 100 emigrants, there were 32 women left behind. In other words, for every 100 married women in Goa, there are five married women whose husbands are away.

Among the women left behind, 71 per cent are Christians, followed by 24 per cent Hindus and five per cent Muslims. Similarly, 75 per cent of women belong to South Goa as against 25 per cent in North Goa. Among the talukas of Goa, the highest proportion of women left behind was found in Salcete (68 per cent), followed by 13 per cent in Bardez and eight per cent in Tiswadi.

Women left behind in Goa are better educated than their counterparts in the general population. According the GMS, 14 per cent of women had completed secondary school against 28.7 per cent among women left behind. Similarly among the undergraduates, the proportion was 27.3 per cent among women left behind as against 10 per cent among the general population. Interestingly, women left behind by the emigrating husbands were well educated as the emigrant women. Among them nearly 55 per cent had a minimum of secondary education and another 26 per cent had an university degree. For instance, the corresponding percentages among emigrant women were: 58.8 per cent with secondary or higher level of education, 36 per cent with an university degree.

This is also true of emigrating husbands. However, some emigrating husbands also marry women who are equally or better educated. For instance, 4.6 per cent of emigrating husbands had completed primary schooling as against 10.3 per cent among wives and 28.7 per cent of both emigrating husbands and wives left behind belonged to the secondary school category.

Though the wives of the emigrant husbands left behind are educationally more qualified than women in the general survey population, their occupational status is dismally low compared to all women in Goa. Most of the women left behind, (85 per cent) were engaged in household activities. Compared to the general female population in Goa, women left behind are more active in the performance of household duties with a difference of 40 per cent. About seven per cent of women behind were employed in the private sector. Nevertheless, 88 per cent of emigrating husbands were engaged in private sector, followed by 10 per cent in self-employment activities. One of the reasons for low employments levels among women left behind is possibly the remittances received from their emigrant husbands.

According to the result of the special GMS, the average age of women who were left behind in Goa was 37.8 years while that of their husbands was about 44 years. About 30 per cent of the women are below 30 years and 20 per cent above 50 years. One-fourth of the women were reported to be in the age group of 25-29 years. The husbands of the women left behind were older by six years. This is slightly higher compared to the age difference between husbands and wives in the general Goan population which is about five years

One out of three married women whose husbands were away, had just completed five years of married life together. In respect of eight per cent of them, their husbands had left them within one year of marriage. Only 40 per cent among the married women had lived with their husbands for more than 15 years before their husbands emigrated. In other words, large proportions of women who were just married or married with small children were left behind to fend for themselves in the absence of their husbands.

However, at the time of marriage, 66 per cent of the husbands were living in Goa; only 33 per cent of the women had husbands who were working abroad. One out of every three women married an emigrant, well aware of the social costs and the economic benefits of the new alliance. Among the 93 women who married emigrant husbands, an overwhelming 98 per cent reported that the marriage took place only because the groom was an emigrant at the time of marriage.

VISITS ABROAD

WHEN we enquired about visits by the emigrant husbands from abroad, 31 per cent of them informed that their husbands never visited them after they had left for employment abroad. About 25 per cent of their husbands visited them only once or twice after their emigration. Another 33 per cent of women reported that their husbands visited more than five times during their employment abroad

Four out of five women left behind never visited their husbands abroad. Among the remaining 20 per cent, 14 per cent visited their husbands just once (probably immediately after marriage), and another six per cent twice. This indicates that most of the emigrating husbands are not earning enough in their destination to be able to take their wives and children along. Therefore it is no wonder that 30 per cent of husbands never visited their wives back home after emigration and that 81 per cent of the wives never visited their husbands abroad.

Among the 53 women in the sample who visited their husbands in the countries of their destination, 25 per cent stayed with their husbands for just one week, another 28 per cent stayed with them for eight days to three months and eight per cent, for more than a year.

COMMUNICATION

THE communication pattern between husbands and wives reveal several interesting features. Communicating with each other (about 74 per cent) over land phone or mobile phone is one of the commonest means of communication between wives left behind and their husbands abroad. About seven per cent used email and 10 per cent used webcam to interact with their husbands abroad. The frequency of communication is high as we see from the following observations from the GMS.

About 16.9 per cent of absentee husbands communicated with their wives every day, 43 per cent once in a week, 13 per cent once in two weeks and 19 per cent only once a month. The mobile revolution on India and abroad has helped the emigrating husband and wives left behind to communicate with each other frequently to relieve their social and psychological tensions.

One of the financial benefits of emigration by husbands is the inflow of remittances from the countries of destination. According to the GMS, 81 per cent of wives left behind reported to have received annual remittances amounting to less than `50,000 and another 16 per cent received between `50,000 to `1,00,000. In about 44 per cent of the cases the mode of transfer of funds was directly through banks; in 33 per cent of the cases the transfer was through cheques and bank drafts. Another 15 per cent of the transfer was through other financial institutions such as the UAE Exchange Centre and Western Union, whereas six per cent of the transfer was through friends and relatives on home visits.

An overwhelming 87 per cent of wives left behind received the remittances in their name, while in 11 per cent of the cases, the remittances were made payable to a parent of the husbands. Again, 71 per cent of wives had full control over the remittances from husbands compared to 21 per cent who had only partial control. One out of ten women whose husbands were away had no control of their husbands’ earnings. In fact, out of 282 women interviewed, 23 women had no control over remittances from their husbands.

When we enquired as to how they managed their households without any financial support from their husbands, 13 per cent of them reported income from property; 30 per cent indicated their own earnings; while 44 per cent were taken care of by their parents, and 13 per cent by their in-laws.

About 56 per cent of wives left behind reported that neither they nor other members of the household held any property. Out of 124 women who reported ownership of property, only 43 per cent held properties in their names; another 49 per cent had joint ownership with husbands and 10 per cent shared the ownership with other members of the households. Regarding the type of property owned, 46 per cent reported possessing land and another 48 per cent reported that they owned houses.

To a query on the source of income for maintaining the household in the absence of the husband, the response was that remittances formed the single source of livelihood among 66 per cent households. Regarding the utilization of remittances, it was found that 47 per cent spent them on meeting day-to-day household expenses and another 29 per cent added the remittances to their savings. Savings out of remittances seem to be much higher among women left behind.

One out of every two women reported that they were in the habit of saving money without the knowledge of their husbands and family. Three out of four women had either a saving account in the bank or post office. 20 per cent of the women contributed to chitties/kuries, which are widely recognized as major instruments of saving.

To assess the women’s autonomy, the GMS canvassed the following information: the question of day-to-day household expenses; expenditure on personal attire such as saris or footwear; purchase of clothes for children; and social visits. When asked who took the decision regarding the pattern of spending more than 80 per cent of the wives reported that they made the decision on their own with regard to the first four items. However, in the matter of undertaking social visits an overwhelming 36 per cent of wives took the permission of their husbands. Evidently, the absence of husbands away from home provides the women with ample opportunities for planning their expenditure. One out of two women had also the benefits of consultation with their more experienced friends.

In the absence of their husbands, women experience social problems. Among them listed in the GMS, loneliness was probably the most acute problem experienced by the young (below 30 years) and old (above 30 years) wives, followed by the burden of shouldering additional responsibilities in the absence of the spouse. Last but not least, they are faced with the specific problem of all pervasive insecurity.

Incidentally, one out of 10 women felt that bringing up children in the absence of husbands was a serious problem. To another question relating to children’s education in the absence of husbands, 38 per cent of women felt that their children would have fared much better in their studies if the father was around. Misbehaviour, disobedience and lack of interest in studies were the three worst problems faced by the women in managing their children.

The GMS also enquired about the relationship that the wives left behind had with their in-laws with whom they had to interact frequently. 20 per cent of the wives reported that their relationship with their in-laws was excellent. Another 38 per cent reported normal relationship, followed by 43 per cent who reported strained relationships. Financial issues appeared to be the most prominent explanation for these strained relationships.

In the event of a member of the household to be rushed to the hospital in an emergency, about 65 per cent of the women reported that they would take them to the hospital; 20 per cent reported that their parents would take the responsibility; and an equal proportion of women said that their in-laws and other family members would take the initiative.

The GMS assessed the social costs and economic benefits of the husband’s migration in terms of satisfaction in life; good and bad experiences. About 27 per cent of the wives reported that they were fully ‘satisfied’ with their life, followed by another 29 per cent who reported ‘very satisfied’. ‘Dissatisfied’ women in all categories were just six per cent.

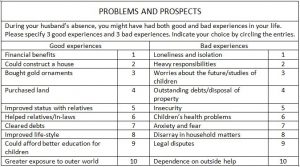

The GMS also listed ten good and bad experiences in the lives of the women whose husbands are away, so as to provide balance sheet on the costs and benefits of emigration (see table below). 80 per cent of the wives reported that the financial benefits were the best outcome. Among the negative factors, an equal proportion reported loneliness, isolation, and heavy responsibilities. In other words, the social costs and economic benefits weighted equally for the wives left behind.

Before leaving the household surveyed, enquiries were made to gauge the overall opinion among the women left behind, with regard to family separation. The question was,” If you have a daughter of marriageable age, whom would you like to marry? Three options were provided: A person working in Goa or a person working outside Goa but within India. Or a person working outside India?” Almost 90 per cent of the women would prefer their daughters to get married to persons living and working in Goa. Only a handful, that is eight per cent, would want their daughters to marry a man who worked abroad. Thus, inspite of the increase in family income through remittances, women who have gone through the trauma of separation from their husbands due to emigration do not want their daughters to go through the same experience.

THE ELDERLY

TO ASSESS the impact of international and internal migration on the elderly in Goa, the GMS canvassed a special module among 1,756 elderly persons of which 962 were male and 794 female. Out of the 1,756 elderly persons, 322 (18 per cent) lived in migrant households where some of the adult members were absent during our survey. The remaining elderly lived in non-migrant households.

Among the elderly surveyed in both types of households, 10 per cent and 13 per cent lived alone in both migrant and non-migrant households respectively, without any married or unmarried sons. According to the GMS, about four per cent of the elderly lived alone in both migrant and non-migrant households. However, about 31 per cent of the elderly live with spouse only in migrant households in the absence of their children who have migrated, compared to 29 per cent in non-migrant households whose children are living away from their house but within Goa itself. Similarly, about 48 per cent of the elderly live with either married sons or married daughters in non-migrants households, while 46 per cent were found in similar living arrangements in the migrant households. Another seven per cent of elderly lived with other relatives (not with any of the living children) among non-migrant households compared to nine per cent among migrant households. Migration, indeed, affects the living patterns of the elderly in Goa.

One out of three elderly persons currently lives in Goa with spouse alone as per the GMS. However, one out of five elderly lives with their spouse and married children (married son or married daughter). Among the elderly who live alone (62 in our sample), 60 per cent live close to their relatives (55 per cent among non-migrant households and 82 per cent among migrant households)

On the question of the best place for the elderly to live at their old age, an overwhelming 42 per cent of the elderly belonging to migrant households said that they preferred to live with their spouse alone compared to 37 per cent among non-migrant household elderly members. About six per cent of them preferred to live alone among migrant households compared to just three per cent among non-migrant households. Similarly, eight per cent of the elderly in migrant households reported that an old age home was the best place for them, although they currently lived in households as against just three per cent among non-migrant households. In fact 11 per cent of the elderly belonging to migrant households were willing to move to an old age home as against eight per cent among the elderly of non-migrant households.

In economic terms, the elderly who belong to migrant households are far better compared to their counterparts. About 41 per cent of the elderly in migrant households own land compared to 31 per cent among non-migrant households. Similarly, 60 per cent of elderly belonging to migrant households reported holding bank deposits compared to just 50 per cent among elderly in non-migrant households. One out of four elderly in migrant households reported remittances as their main source of income.

The elderly in migrant households live in a comparatively better housing environment, with bath-attached bedrooms and sleeping arrangements suitable to their age. For instance, about 47 per cent of the elderly in migrant households reported their sleeping arrangements as ‘good’ compared to just 29 per cent in non-migrant households.

The current state of the health of the elderly differs between migrant and non-migrant households. 41 per cent of the elderly in the migrant households reported their current state of health as ‘excellent or good’ as against 29 per cent among the non-migrant households of the elderly. 39 per cent of the elderly living in migrant households preferred to visit private hospitals for treatment compared to 29 per cent in the non-migrant households.

When enquired about any ailment/injury/accident experienced during the current month among the elderly in Goa, 11 per cent of the surveyed elderly reported as episode which led them to consult a doctor and to pay for diagnostic tests and medicines. The average cost incurred by the elderly belonging to migrant households works out to be `4,955, almost double when compared to `2,997 among non-migrant households.

When enquired about any ailment/injury/accident experienced during the current month among the elderly in Goa, 11 per cent of the surveyed elderly reported as episode which led them to consult a doctor and to pay for diagnostic tests and medicines. The average cost incurred by the elderly belonging to migrant households works out to be `4,955, almost double when compared to `2,997 among non-migrant households.

Similarly seven per cent of the surveyed elderly in Goa had been hospitalized during the previous due to ill-health. In 2008, on an average, the elderly in Goa had to spend `24,798 or their in patent treatment such as consultation, diagnostic charges, medicines, room rent, travel and other related costs. However, the average cost is `37,227 for the elderly living in migrant households compared to `21,431 among non-migrant households Regarding the use of aids to manage handicaps in walking, seeing, or hearing, 44 per cent of the elderly belonged to migrant households and could afford to purchases such aids as against 32 per cent among non-migrant households. Similar differences were reported in the case of affording to smoke (14 per cent of migrant households as against 11 per cent among non-migrant households), and affording alcoholic drinks (17 per cent among migrant households as against 11 per cent among non-migrant households)

In short, while emigrants bring remittances, and the women and the elderly left behind are economically well off and enjoy all economic benefits, socially, they are isolated, lonely, and burdened with other additional responsibilities.

Excerpt from Goa Migration Study 2008, published by the Department of NRI Affairs, Government of Goa