By Supercop Julio Ribeiro

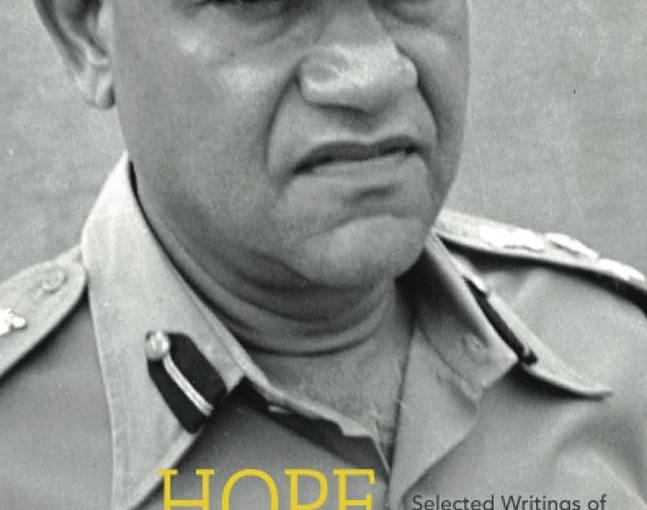

WHO has not heard of India’s supercop Julio Ribeiro? Time you did if you haven’t and get hold of his book Hope for Sanity’ published by Yoda Press, softcover, Rs499 and understand his message of how India is going the Pakistan way…is it? Julio Ribeiro, former police commissioner of Mumbai, Director General of Police in Gujarat and Punjab, and who knows Bombay that is Mumbai like the back of his hand, also the country at large, thinks India is going the Pakistan way. Read the “proof” in his bookHope for Sanity,’ a collection of his writings which document a vital part of this country’s modern-day political history very succinctly.

Julio Ribeiro was here in Goa to say hello to family and friends — and for the release of his book which is a compilation of his selected writings from 2002 to 2021. This is one very tough, sensitive and sensible supercop, would be hard to find in our times today! If we may say so it takes guts to take on Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his ruling BJP government which came to power on a democratic platform 14 years ago but many now think this platform is crumbling in the interests of one-party rule or dictatorship!

We need to read up JF Ribeiro to understand and remember how democracy turns to dictatorship. We salute a man whom we have come to call supercop with utmost respect and affection, may he be protected with many blessings!

Excerpted from `Hope for Sanity,’ selected writings of Julio Ribeiro…

Three Incredible Stories of Corruption

This article first appeared in the Tribune India on 6 June 2020

This week, I write about corruption. In my post-retirement avatar of social activist, I came across many cases of corruption, three of which I proceed to recount.

Case 1

Rajamani Iyer has been a good friend since 1944 when we joined Sydenham College as first-year commerce students. Rajamani’s son, Shyam, was accused of an economic crime which he insisted he had not committed.

The police took their time to complete th inquiry and kept Shyam in judicial custody for many months. When at last he was granted basil, the court rejected the cash deposit he offered. Shyam produced his father’s fixed deposit receipts which were also rejected. His father owns a flat in Matunga, valued at over Rs1 crore. That surety was also rejected. Three weeks had elapsed since the sanction of bail, but Shyam continued to languish in Arthur Road Jail.

Finally, two unknown, probably professional, sureties were introduced to Shyam by those who hover around the courts. They stood surety for him on cash payment of the bail amount plus 75 per cent extra for their services!

I wrote to the Chief Justice of the Bombay High Court, asking her to inquire into this patently irregular method of approving of sureties. I got no reply, though I presume Chief Justice Chellur must have ordered an inquiry. What resulted from the inquiry, I do not know. A year after my complaint to the high court, Shyam died in an accidental fire at his residential flat in Colaba.

The sheer impunity with which corruption is ingrained in the grant of bail is truly mind-boggling. Why do we complain of shortage of judges and crowding of jails if we condone institutionalised corruption which can easily be abolished if the higher judiciary puts its food down?

Case 2

In December 1993, on my return to Mumbai after eight and a half years, I was approached, among others, by a charitable organisation known as the Happy Home and School for the Blind, established and run by kind hearted Parsis to care for 200 blind boys. Almost all these boys come from very poor families. They belonged to different castes and creeds.

The government had allotted a piece of prime land in Worli at a token leasehold rent of Rs1 per year. We were not permitted to make commercial use of the land or allow anything to be built on that land. Yet, one of the previous chairmen had wrongly given part of the ground floor to a restaurant, at a very nominal rent. It was shown as a canteen for the blind boys, which was patently untrue.

Justice Hidayatullah, a former Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of India and former vice-president of India, was the chairman of the institution when the government served notice on the Happy Home management for a breach of the terms of the lease.

Justice Hidayatullah went through the papers and opined that the Home was guilty of contravening the law. Happy Home served notice on the restaurateur to vacate. The restaurateur went to court and was granted a reprieve of 10 years to wind up its operations.

Before these 10 years were over, Justice Hidayatullah died and I succeeded Justice Bakhtawar Lentin as chairman. The restaurateur was an influential man with contacts at the highest levels of government. He approached us with an offer of Rs40 lakh, which he said we could use for building an extra floor, so as to allow him to continue operating his restaurant on the ground floor.

I pointed out to him that we were not permitted to rent out any space on our premises as the land was a leasehold. His answer was that he would managed the government! We refused.

Imagine our surprise when we received an order soon thereafter from the government cancelling our lease and transferring it to the restaurant magnate! I met the Chief Secretary in his office and threatened to sit on the public road along with the 200 blind inmates of Happy Home. Simultaneously, we filed a write petition in the Bombay High Court, which we easily won. Navroz Seervai, our `pro bono’ lawyer, remarked that in the course of his career in law, he had not come across an instance of such gross corruption. The government of the day was a Shiv Sena-BJP one led by Narayan Rane, who had passed the order.

Case 3

To partly meet our expenses Happy Home and the School for the Blind had sought grants from the government to pay the teaching and non-teaching staff. In return, we had to invite the Social Service Department of the government to sit in at interviews when our principal selected teachers and staff. We thought that this would help the school to be more perceptive in the process of selection, but our experience was just the opposite. We had to accommodate a few useless and troublesome individuals who were suggested by the Social Service Department for the posts! The representative of that department had signed off on the minutes of the selection committee’s meeting. Two candidates not recommended by the department were also selected. Their work was really praiseworthy.

Imagine our surprise when three or four years down the line, the department informed us that the selection process did not conform to rules and these two were not entitled to be paid from government funds! A lengthy correspondence ensured. The minister was approached. All attempts were made to address the Social Service Department’s objections, but finally the two staff members had to pay the officer-in-charge Rs5 lakh each to regularize the selections previously approved by the same department.

At one state, I had approached Pravin Dixit, Director, Anti-Corruption, and arranged to trap the officer concerned, but the teachers and Happy Home’s trustees did not approve of y plan because they were concerned that the consequences would be disastrous for the institution.

These three instances of corruption that I had to personally deal with have convinced me that fighting corruption needs political will at the highest levels of government.