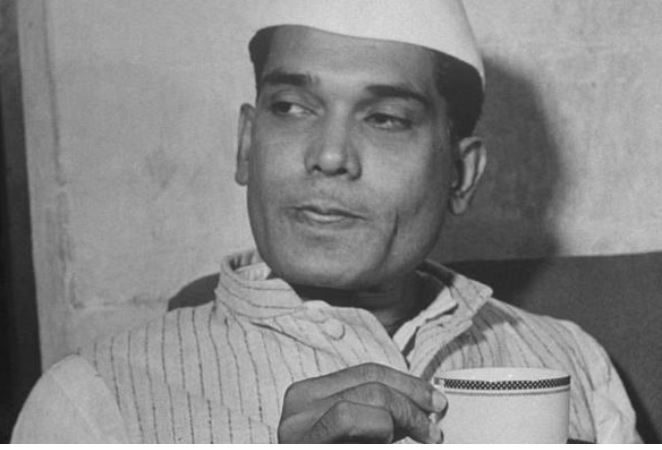

On 8 June 1969, Jayaprakash Narayan addressed the National Conference on Voluntary Agencies at the Gandhi Peace Foundation in New Delhi where he said he sympathised with Naxalites because they are ‘doing something for the poor’.

By Jayaprakash Narayan

What are the revolutionary changes that have taken place in India since independence? Only two changes have seeped down to the roots of the Indian society. One is the abolition of princedom and the other the abolition of the zamindari system. Zamindari has been destroyed from the roots. But for the rest, feudalism has firmly entrenched itself especially in ex zamindari areas and a capitalist society has come into being, in spite of all the talk of socialism and communism. Though the roots of feudalism have been destroyed with the destruction of the princely order and the zamindari order, no socialist society has come into being during the past twenty-two years.Feudalism is entrenched in the rural society. It is everywhere—in U.P., in Bihar—except, perhaps, in the ryotwari areas where it takes a different form. But it does exist there too, though not in the same virulent form or elsewhere. Even if you nationalise, capitalism is there. In nationalising, what do we do? Is there any basic fundamental change in the public sector except the change in ownership and, therefore, in the distribution of surplus or profit? Except for that, what is the status of labour? What about industrial relations? This is not socialism. This is bureaucratism. There is no fundamental change. I have begun to doubt very seriously whether any government is going to bring about a radical social revolution in India through democratic means. When the first non-Congress Government came to power in Bihar, I made some proposals to those people. During those ten months, not an inch of progress was made towards any of these things.

Take the case of share-croppers. We hear about the Naxalites. I have every sympathy with the Naxalbari people. They are violent people. But I have every sympathy with them because they are doing something for the poor. There is some limit to the patience of the people. Why cannot the question of share-croppers be settled? The law gives them certain rights. After they cultivate a piece of land for so many years, they get occupancy rights and they cannot be evicted. But in Bihar and Bengal the landowner is free to evict them, and he does evict them. What do you think is happening in Purnea and other areas? Thousands of share-croppers are being evicted because the landowners have the right to resume the land; because these poor people do not have even a chit to prove that the land was in their cultivating possession. They cannot prove it in a court of law. These things are happening today and the law is absolutely impotent to help these poor people.

If the law is unable to give to the people a modicum of social and economic justice, if even whatever is on paper is not implemented, what do you think will happen if not violence erupting all over? Do you think that mere mantras of shanti are going to save the situation of the political parties which are responsible for this legislation? The very people who pass these laws have seen to it that the laws are not implemented.

I find that the people are losing hope and they feel that nothing will come out of any government. When I see the situation of Bihar I also begin to share their feelings. One after the other changes in the government have taken place but nothing has changed.With all the programmes and activities in this Gandhi Centenary Year, if the problems of the people are not solved democratically, what other recourse will the people have except violence? Therefore I say, what India needs today on her political agenda is non-violent social revolution. Not only from the moral point of view but also from the practical point of view, this is one of the essential items on the political agenda of India today. Otherwise, violence will grow. I don’t care about the Naxalite movement. This is going to grow.

I have been a student of revolutions because I was a Marxist myself. My interest in the history of revolutions is as keen today as it ever was. My conclusion after a study of violent revolution is that a violent revolution does bring about a revolution in the sense that it uproots the old social order and destroys it from its foundation. Therefore it is looked upon as a successful revolution. But it fails in achieving the objectives for which the revolution is made. The French Revolution was a great revolution. After that many revolutions have taken place. There was the American Revolution. Undoubtedly the feudal system was destroyed from its roots.

As a result of the experience of democratic societies in other parts of the world and of democratic government in our own country, I have begun to doubt on the one hand whether social revolution can be brought about by democratic means and, on the other, I reject violence as only half the revolution. The more important half of it is the betrayal of the people.

I don’t want power for myself; I want power for the people. Therefore, I cannot support the Naxalites and I hope to persuade them at some point of time or the other. If they want power for themselves and/or the Communist Party, Marxist-Leninist, then it is all right and let them do what they wish. But I would not agree with this. Shri Jyoti Basu said at a recent workers’ meeting in Calcutta: ‘I want factories to be given to the workers.’ I would like to know in which Communist country the factories belong to the workers. Not a single factory belongs to the workers in any Communist country except, in some respects, in Yugoslavia which the other Communists do not accept as a proper Communist country. The factories belong to the state. They dupe the workers. They say, ‘the state belongs to you’, as if the workers can do anything with the state. This is the kind of dictatorial set-up that we find in the Communist countries. Where do we go? It is here that Gandhi had something to say.

This is part of ThePrint’s Great Speeches series. It features speeches and debates that shaped modern India.

This edited excerpt from ‘The Great Speeches of Modern India’ has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.

Courtesy; The Print