Goa is abuzz with excitement as vintage bike and car owners, users, collectors and fans are decking […]

PORTRAIT OF THE ARTISTE AS ACADEMIC – AND DALIT! By Prema Viswanathan

Art & Culture, Sep 06- Sep 12, 2025 September 5, 2025At 13, dire poverty drove Senrayaperumal to leave school to join his family’s folk theatre troupe in Soolapuram. Decades later, armed with a PhD, he was ousted from his teaching job — and forced to go back to that same penurious existence. His story, captured in the documentary “Punishing the Professor,” resonates far beyond Tamil Nadu, echoing the struggles of Dalit scholars across India.

ON A still Sunday evening at the Bangalore International Centre, the hall fell into hushed silence. At the close of the documentary “Punishing the Professor,” the film’s protagonist — folk performer turned academic P Senrayaperumal, turned to the audience, a tentative smile lighting up his face. His voice, deep and resonant, unfurled into song.

He sang of his mother. Annee, he called her in Tamil, each note weighed down with the grief of an orphaned son. The melody swelled, filling the space with a sorrow too vast to be contained by one man alone. In that moment, personal loss transformed into collective lament — the grief of a community long disenfranchised, struggling to claim its rightful place in the world.

It was an ending more powerful than any film could script.

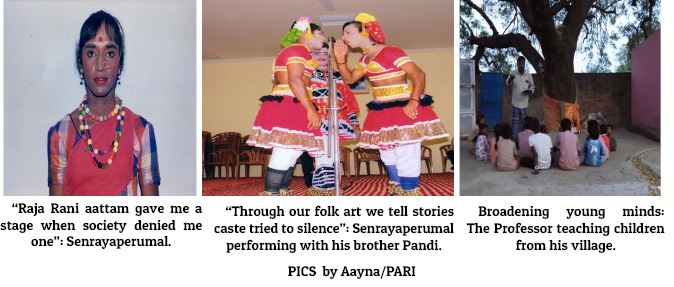

FOR Senrayaperumal, art was never mere performance. It was survival, identity, and defiance. Born in Soolapuram village, 60km from Madurai in Tamil Nadu, he inherited folk forms that pulsed with history and memory. The art form he carried forward has for generations been nurtured by the Arunthathiyar community, the Scheduled Caste group to which he belongs. In their hands, performance became both livelihood and assertion: a culture preserved in the face of indifference, stigma, and erasure.

At 13, that inheritance became his destiny. He was in Class 7 when he was compelled to drop out of school and train to be a dancer and folk artiste. “I knew I would be asked to stop going to school at some stage,” he recalled.

With eight mouths to feed, his father, K Perumal, needed him to join the family’s folk theatre troupe, the Soolapuram Sinna Set, and began the task of initiating his youngest son into the intricacies of the art form. Senrayaperumal’s three older brothers were by then already accomplished folk artistes, while his two older sisters were wage workers on the farm.

NO CAKEWALK

BUT life as a folk artiste was no cakewalk. The daily regimen was relentless and the returns meagre. “The Rs35,000 we make per show is split among all the performers, and a large portion goes towards travel,” explained Senrayaperumal. And the troupe works barely six months in a year. “Rice was a luxury, we would be served millet porridge most days for lunch,” he said. It was, and remains, a frugal existence — one that the unemployed professor (now father of a two-year-old boy) has been forced to return to, the cycle of art and want repeating itself decades later.

It was not just poverty he had to contend with, but also caste-based indignities. “In some villages dominant caste people would ask us to sing casteist songs. If we refused, they would not pay us. And not just that. We wouldn’t even be served water in these villages as we belonged to the oppressed caste.”

For Senrayaperumal, the stage was both inheritance and burden. Art runs in his blood. His grandfather was a folk artist; his father played female roles on stage. But in his part of the country, Dalit families were barred from using caste Hindu wells; children like him had to fetch water from afar, carrying the weight of exclusion.

From this morass of injustice Senrayaperumal carved a path into academia, turning lived practice into scholarship. His appointment as a professor should have been adequate proof of the promise of education — its power to lift, to transform, to redress. Instead, that promise collapsed under the weight of rules and prejudice.

“I didn’t have an opportunity to finish my 10th and 12th like others,” he recalled. But he persisted — undergraduate, MA, MPhil. Each degree was earned against the odds, stitched together from fragments of opportunity.

HE THEN went on to acquire a PhD in Art History from Madurai Kamaraj University through the open university system, after pole vaulting to university straight from Class 8. Testimony enough of his perseverance in navigating the long corridors of India’s educational bureaucracy. Yet when he finally found work in 2016, it was not as a professor of art but as an assistant professor in the Department of History at Manonmaniam Sundaranar University (MSU) in Tirunelveli. It was here, in a modest post far from the cultural spotlight, that his expertise as both performer and scholar first entered the classroom.

But that access to academia did not endure. After eight years of service, he was arbitrarily removed from the post on March 23, 2024 — the system that had briefly embraced him turning its back on him with unexpected finality.

After his removal, Senrayaperumal approached the courts, petitioning for the dismissal order to be withdrawn. The Madras High Court concurred with the rationale of his plea, instructing the university to reinstate him — a verdict that seemed, briefly, like justice catching up at last. But that hope was swiftly undone. The university syndicate, invoking University Grants Commission (UGC) rules, voted to appeal the decision. What the court had sought to restore, the institution moved to deny once more.

IT WAS back to the beginning. From performer to professor to performer again. But even the stage could be perilous. In the Raja Rani genre — a centuries-old folk theatre in which men don the costumes of women to enact the flamboyant dance of royal lovers — he often faced hostility. Some male spectators, steeped in their own entitlement, jeered or taunted him, their toxic masculinity turning performance into confrontation. For Senrayaperumal, every appearance in costume was not only an act of art but of courage — a negotiation with contempt, a refusal to yield to derision.

When I spoke with the Vice Chancellor of MSU, Professor N Chandrasekhar, he admitted to sympathy but insisted his hands were tied. “Personally, I feel for him,” he said. “But the syndicate’s decision prevails. My personal views don’t come into the picture.”

The syndicate he chairs includes professors as well as government secretaries. The majority voted to challenge the order to reinstate. “That decision was taken before I took over as VC. My job was just to act on the decision,” he said. Under UGC rules, disruption in formal education disqualifies a candidate for a teaching post. “His appointment was an aberration,” the VC explained, “and the UGC has since corrected it. There will be no more such appointments.”

His words were couched in the language of procedure — rules standing in for justice, sympathy caged within bureaucracy. Even as he conceded the hardships borne by the community the professor comes from, he drew a line: as administrator, he said, he could not bend the machine of regulation.

Senrayaperumal has not allowed the bureaucratic stonewalling to dampen his resolve. He met Tamil Nadu Chief Minister MK Stalin, who instructed the State’s education minister to secure his reinstatement. Yet so far the university syndicate has been unyielding, a reminder of how deep institutional resistance can run.

Senrayaperumal’s ordeal is not an isolated one. A recent report by The News Minute (July 10, 2025, by Samrah Attar) documented how Dalit professors at Bangalore University alleged systemic discrimination in both appointments and compensation. The resonance between their testimonies and Senrayaperumal’s struggle is stark. Across state lines, the story echoes the same refrain: caste continues to shadow the lecture hall as much as the stage.

IF the university closed its doors, others opened theirs. “I am deeply grateful for the moral support from PARI and P Sainath, its founder editor,” Senrayaperumal told me, pointing to the People’s Archive of Rural India, which first chronicled his journey. Filmmaker Aayna, who captured his story in “Punishing the Professor,” works with PARI herself. She recently won the prestigious Dayanita Singh–PARI Documentary Photography Award — recognition for a lens that has preserved what institutions attempted to erase.

In the wake of the documentary, gestures of solidarity have emerged from the world of law as well. “I’m grateful for the support of Hon’ble Chief Justice (Retd) Dr S Muralidhar, now a senior advocate in the Supreme Court, who has volunteered to appear in court for me pro bono,” Senrayaperumal said. In the dry corridors of litigation, such generosity is rare indeed.

At the August 31 screening in Bangalore, after the lights came back on, I spoke with both Senrayaperumal and Aayna. The weight of the professor’s ordeal sat alongside his quiet dignity; the filmmaker’s conviction lent it urgency. Together, their words echoed what his song had already carried into the room: that this was not only about one man’s reinstatement. It was about memory, erasure, and the fragile lifelines of solidarity that stand against both.

IN the end, it is his voice that lingers. A song to a mother, a lament for a community, a challenge to a system that measures worth only in certificates while ignoring resilience, artistry, and lived knowledge.

And so the professor sings. Each note binds the past to the present: the boy walking home from school for the last time, the scholar dismissed from his post, the performer taunted on stage. Woven together, they form an unbroken thread — fragile, defiant, and enduring. In that thread lies a promise: that neither he, nor the people he represents, will be silenced.