Goa is abuzz with excitement as vintage bike and car owners, users, collectors and fans are decking […]

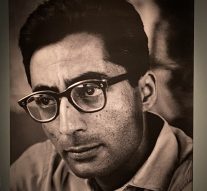

From Word to Image: The Inner Worlds of Ram Kumar

Uncategorized November 7, 2025By Prema Viswanathan

Three decades ago, I had written of Ram Kumar’s journey “from Marxism to pantheism” — the odyssey of a painter who began with the anguish of the worker and ended with the quietude of the mountain.

Reading his letters today, one realises that the transformation was not abrupt but marked by the slow rhythm that characterised his attitude to life and art. The terrain he painted was always, in some sense, the terrain he wrote about — landscapes of thought and solitude, the space between word and image.

That connection was brought vividly to life in Shape of a Thought: Letters from Ram Kumar, an exhibition curated by Arnika Ahldag and Priya Chauhan at the Museum of Art and Photography, Bengaluru, which ended on October 26. For the first time, viewers could encounter the artist’s handwriting — the slant, the hesitation, the fragile conviction of line — beside the canvases that emerged from the same inner meanderings. The show revealed the letters not as marginalia but as parallel works: essays in tone, rhythm and introspection that mirrored the evolution of his visual idiom.

In early 50s Paris, under Fernand Léger, the young Ram Kumar learnt not merely the mechanics of Cubism but the courage to experiment. He joined the French Communist Party, read Paul Éluard and Louis Aragon, and found solace in the idea of art as a moral act. “They were tumultuous times,” he later recalled to me. “I could not wait to translate my faith into practice.”

His early canvases — The Worker’s Family, Sorrow, The Family — bear the weight of that faith. They are peopled by the faceless poor, compressed within a geometry of hopelessness. Yet his letters from the period already suggest a tension between empathy and exhaustion. “I paint them because they haunt me,” he wrote, “but perhaps one day I will paint the haunting itself.”

That haunting — the mood, the silence, the echo — would become his true subject. What began as the alienation of man in the city turned, gradually, into the loneliness of the soul in the cosmos. His move from figuration to abstraction was not a rejection of humanity but its sublimation. In one letter, he confessed: “Perhaps the man has vanished, leaving behind only his presence — like breath upon glass.”

The letters reveal how painting and writing were twin disciplines of introspection. Trained first as a writer — his Hindi short stories in The Sea and Other Stories (1997) trace the same inner restlessness — he often used the act of writing as a way to clarify vision. “When the world becomes too much,” he wrote, “I write until I can see again.” Words became a kind of sketchbook, a preliminary drawing in thought before line and colour took over as language.

Like Van Gogh’s letters to his brother Theo, Ram Kumar’s correspondence records an artist in dialogue with himself. Van Gogh wrote that he painted “things for which there are no words.” Ram Kumar, by contrast, wrote in order to reach the point where words would dissolve into silence. Both men turned to language not to explain art but to survive its demands. “I must paint,” Ram Kumar wrote from Delhi in the late 1950s, “otherwise the city will crush me. Writing helps me breathe till the colours come.” In another letter, he spoke of his walk through Humayun’s tomb and of the monument “looking very lovely as death is.”

The continuity between his letters and paintings can be read in several ways.

First, both trace an inward migration — from the crowded street to the still riverbank, from the social to the metaphysical. His early writings bristle with the vocabulary of struggle; later, they meditate on serenity. The shift mirrors his visual trajectory from the anxious worker to the contemplative ghat.

Second, both disciplines favour essence over appearance. Just as he pared the figure to a few delicate lines, his letters discard ornament for candour. “It is not what I describe,” he once wrote, “but what remains unsaid between the sentences that matters.”

Third, both explore the poetics of silence. Ram Kumar’s letters, like his late canvases, are full of pauses — hesitant, elliptical, more rhythm than argument. He wrote as he painted: through restraint.

And finally, both reflect a humanism without the human figure. After the 1960s, his paintings emptied themselves of people, yet retained the pulse of life through their surfaces — the bruised earth tones, the fugitive greys and ochres, the delicate gradations of despair and release. His letters from the period are similarly unpeopled: they speak not of events but of sensations — a dawn light on the ghats, the hush of prayer, the “unbearable beauty of emptiness.”

When Ram Kumar travelled to Varanasi in 1961 with M. F. Husain, the encounter marked a turning point. “For Husain, human suffering was to be painted through the face,” he told me. “For me, no human face could encompass that scale of pain. Only the landscape could.” His letters from that trip are suffused with wonder and dread. The river becomes a mirror of impermanence, the ghats a metaphor for both decay and deliverance. “I felt as if I was painting death,” he wrote, “but it did not frighten me. It was a calm death, the kind that leads to light.”

The ghats became, thereafter, his psychic landscape — a geography of detachment. In his later series on Ladakh, the mountains assume the purity of an inner discipline. The pilgrim of Marxism becomes the monk of abstraction. Yet, the letters show, he never ceased to feel compassion for the human condition. “Abstraction,” he wrote, “is not escape. It is the condensation of all experience into one breath.”

Three decades after I interviewed him, what strikes me anew is how closely his writing shadows his art. Both are ascetic, yet deeply sensuous; both move from turmoil toward stillness. In a letter to a fellow artist, he described painting as “a journey toward the moment before speech.” The phrase could stand as a summation of his life’s work — an art poised on the threshold between word and silence, memory and erasure.

If Van Gogh’s letters are the autobiography of passion, Ram Kumar’s are the autobiography of restraint. In both, the human voice trembles between confession and transcendence. The difference lies in tone: Van Gogh’s fevered urgency becomes, in Ram Kumar, a deliberate quietude — the calm that follows revelation.

To read his letters alongside his paintings is to perceive their unity: the letter as the sketch, the painting as the distilled epiphany. Both are haunted by absence — not a void, but a plenitude so vast that the self dissolves within it. The man who once painted the worker’s family ends his career painting the horizon. Yet, even in the emptiest canvas, one feels the trace of human breath.

In one of his last recorded reflections, Ram Kumar wrote: “The artist’s task is to dissolve — to become the wind, the river, the silence after sound.” His words bring to mind the painter’s own terrain — those spectral cityscapes and barren ghats where the boundary between matter and spirit blurs into mist.

Between word and image, Ram Kumar found not contrast but continuity — two languages seeking the same truth. The letters give us his struggle; the paintings, his release. Together they form an unbroken meditation on the only landscape that finally mattered to him — the landscape within.