Goa is abuzz with excitement as vintage bike and car owners, users, collectors and fans are decking […]

WATER-BORNE DISEASES: LESSONS FROM THE INDORE TRAGEDY! By Dr Amit Dias

Jan 10- Jan 16, 2025, MIND & BODY, HEART & SOUL January 9, 2026THE recent water contamination tragedy in Indore, which led to multiple hospitalisation and the tragic loss of life, has woken up the nation to confronting a reality it prefers to ignore. All that shines is not gold. Dr Amit Dias simplifies this for us through this article while providing the roadmap to prevent such incidents.

WATER nurtures life, fuels growth and sustains human survival, but when polluted, it turns treacherous. Unsafe drinking water can carry several water-borne diseases, caused by a vast array of disease-causing microbes, transforming a basic necessity into a public health threat. A city can look clean on the surface and still fail at its most fundamental public health obligation — providing safe drinking water. Indore, often celebrated as India’s cleanest city, has become an unsettling reminder that urban hygiene rankings do not automatically translate into water safety.

This was not a sudden or unpredictable disaster. Reports of foul-smelling, discoloured water flowing from household taps had surfaced weeks earlier in affected localities, which should have sent alarm bells. It’s true that we all grow in wisdom in hindsight, and a lot of what could have prevented this looks very basic. But we should not ignore it and let this repeat in the future in any city in the country.

What happened was — acute diarrhoeal illness, dehydration and deaths — a grim replay of a pattern India has seen far too often. The Indore incident must therefore be viewed not as an isolated mishap, but as a warning signal for every Indian city.

The Silent Burden of Unsafe Water

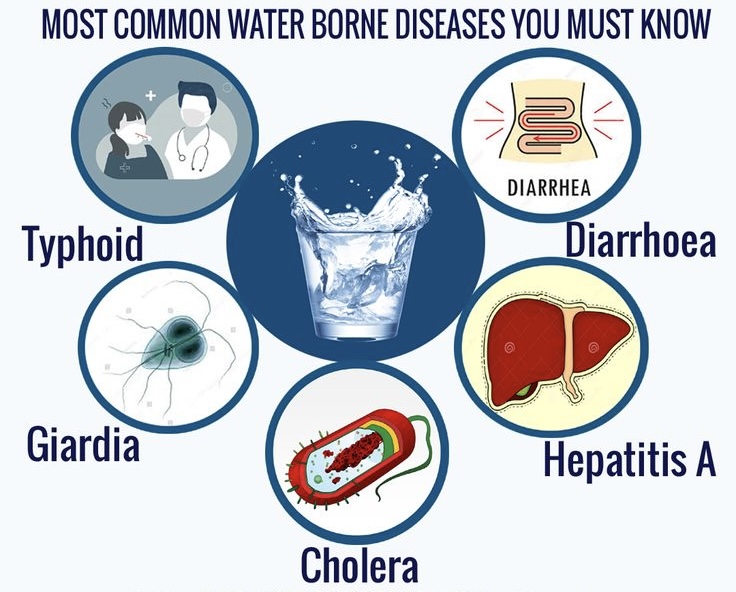

UNSAFE drinking water remains one of India’s most persistent and preventable public health threats. Each year, lakhs of Indians suffer from diarrhoeal diseases, typhoid, hepatitis A and E, cholera, and other water-borne illnesses. Children, the elderly, pregnant women, and urban poor communities are disproportionately affected. While many survive, repeated infections contribute to chronic undernutrition, poor cognitive development, lost productivity, and mounting healthcare costs.

Globally, contaminated water is responsible for over a million deaths annually. India carries a significant share of this burden. According to international assessments, India ranks around 120th out of more than 120 countries in global water quality indices, reflecting serious challenges in both chemical and microbial safety. Nearly 85% of India’s drinking water depends on groundwater, much of which is threatened by over-extraction and contamination with fluoride, arsenic, nitrates, iron, and heavy metals. Let’s look at the Indore incident as a case study.

Indore: A Case Study

THE Indore tragedy highlights a structural weakness common to many Indian cities — aging water infrastructure. Much of urban India still relies on pipelines laid decades ago, and for reasons unknown, often running parallel to or crossing sewage lines. Leakages, negative pressure during intermittent water supply, and poor maintenance create ideal conditions for sewage to seep into drinking water networks.

Investigations following the Indore incident reportedly pointed to pipeline leakages and sewage contamination —what public health professionals describe as the basics of urban water safety. We had a similar incident some years ago in Panaji, where the sewage pipeline contaminated the water pipeline, leading to an outbreak of Hepatitis E and A. Remember water does contain residual chlorine to the extent of 0.5 ppm, but that is not enough to kill the hepatitis viruses and other microorganisms.

The tragedy underscores a critical lesson: water safety is not merely about treatment at the source but about safeguarding the entire chain — from source to tap.

Beyond Germs: The Chemical Threat in Our Water

WHILE outbreaks draw attention to microbial contamination, chemical pollution poses an even more insidious danger. Large populations in India are chronically exposed to toxic elements in drinking water. Arsenic contamination in eastern India represents one of the world’s largest mass poisonings, linked to skin lesions, cancers, and cardiovascular disease. Fluoride causes skeletal fluorosis, mercury damages the nervous system, lead impairs childhood brain development, and excess nitrates can be fatal for infants.

Industrial effluents, agricultural runoff, and untreated sewage continue to degrade rivers and groundwater. These pollutants accumulate silently, often going undetected until irreversible harm has occurred.

Providing safe water:

IT IS important to acknowledge that India has prioritised this issue. Over the past decade, several major initiatives have sought to address water access and quality.

The Jal Jeevan Mission (JJM), launched in 2019, aims to provide functional household tap connections with adequate quantity and prescribed quality of water to every rural household. The mission has significantly expanded coverage, transforming water access in many regions.

Complementing this, the Swachh Bharat Mission has reduced open defecation and improved sanitation, indirectly contributing to safer water sources. The National Rural Drinking Water Programme, AMRUT (Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation), and investments in sewage treatment plants and river rejuvenation projects reflect a growing recognition of the water-health nexus.

India has also strengthened laboratory networks for water quality testing and issued drinking water quality standards aligned with international norms.

Yet, access alone is not enough.

The Missing Link: Water Safety and Surveillance

THE Indore episode reveals a policy imbalance — an emphasis on coverage and visible cleanliness, with insufficient attention to continuous water quality monitoring and distribution safety. Real-time surveillance systems capable of detecting microbial and chemical contamination at the source, during distribution, and at household taps remain limited.

Citizen complaints are often treated as service grievances rather than early warning signals of public health risk. Inter-departmental coordination between urban local bodies, water utilities, and health departments is frequently weak, delaying response and accountability.

Households as the Last Line of Defence

IN this context, household-level precautions play a crucial role. Boiling water remains one of the most effective methods for eliminating pathogens. Safe storage practices — clean containers, covered vessels, and avoidance of hand contact — are equally important.

Water purification technologies have become widespread. Gravity-based filters remove suspended impurities, UV systems inactivate microbes, and reverse osmosis units are effective against dissolved salts and heavy metals. However, these systems require regular maintenance and should complement — not replace — safe public water supply.

Travelling and Water Safety:

TRAVELLERS face heightened risks, especially during outbreaks and in areas with uncertain water quality. Drinking sealed bottled water, avoiding ice and raw foods, using safe water even for brushing teeth, and preferring freshly cooked meals can prevent most water-borne illnesses. Vaccination against typhoid and hepatitis A provides added protection for vulnerable groups.

Policy Prescriptions: The Way Forward

THE Indore tragedy must catalyse a shift from cosmetic success to substantive public health protection.

First, water safety plans should be mandatory for all cities, integrating source protection, treatment, distribution integrity, and community feedback. Second, real-time water quality monitoring, with publicly accessible data, must become the norm rather than the exception. Third, urban pipeline infrastructure urgently requires upgrading, with clear physical separation between sewage and drinking water networks.

Equally important is governance reform. Urban local bodies need dedicated financing for water quality laboratories, rapid response teams, and preventive maintenance — not just crisis management. Citizen complaints must trigger time-bound investigation and corrective action.

At the national level, programs like the Jal Jeevan Mission should increasingly focus on assured quality, not merely connections. Water safety indicators must be embedded into city rankings and performance assessments.

A Wake-Up Call for India

THE history of public health offers a powerful lesson: the greatest gains in life expectancy came not from hospitals, but from safe water, sanitation, and hygiene. Europe’s cholera epidemics of the 19th century transformed urban water systems and laid the foundation for modern public health.

India now stands at a similar crossroads. The Indore water tragedy is a reminder that clean streets and awards cannot compensate for contaminated taps. Safe drinking water is not a technical luxury or political slogan — it is a constitutional obligation and a basic human right.

If India is serious about becoming a developed nation, it must ensure that no citizen risks illness or death from the simple act of drinking water. The real measure of a city’s cleanliness lies not in its rankings, but in the safety of every drop its people consume.