Goa is abuzz with excitement as vintage bike and car owners, users, collectors and fans are decking […]

FROM SUMI INK TO SCHIELE’S LINE: THE GLOBAL CANVAS OF ASIT PODDAR!By Prema Viswanathan

Art & Culture January 30, 2026For Asit Poddar, a canvas is never just a surface; it is an intersection where the jagged lines of Austrian painter Egon Schiele meet the meditative silence of Japanese ink. To speak with Poddar is to travel through a map of the 20th century—from the trauma of Partition in East Bengal to the sun-drenched canals of Venice and the stark, spiritual banks of the Ganges.

The recent exhibition of Poddar’s work in Bengaluru, showcased at the Venkatappa Art Gallery by the Time and Space Gallery, created a meaningful bridge between two artists: K. Venkatappa, who pioneered early modernist idioms in South India, following his training under the Bengal master Abanindranath Tagore, and Poddar, who carries a related lineage into a global, itinerant context. The gallery therefore offered a fitting setting for Poddar’s multi-medium works, highlighting his subtle watercolours and dense Sumi ink surfaces.

THE SHADOWS OF HISTORY AND THE SEARCH FOR PLACE

Poddar’s journey began in the crucible of displacement. Originally from a village near Dhaka, his family fled during the Partition to escape targeted attacks. This early loss of home explains his lifelong wanderlust—a search for “place” that has seen him spend months in Europe every year for the last quarter-century. While he remains a secular voice, he speaks with a heavy heart about the shifting cultural landscapes in his ancestral home, noting how modern aggressions threaten the pluralistic fabric of the Bengal he remembers as also of today’s India.

THE SCHOOL OF PERFECTION: SATYAJIT RAY

If Partition shaped his soul, filmmaker Satyajit Ray shaped his eye. In 1979, Poddar worked as an assistant on Ray’s Hirak Rajar Deshe.

“What I learnt from Ray is to strive for perfection,” Poddar recalls. “He chose the best people… his cinematographer was among the best in the world.”

This apprenticeship in precision taught him that art requires an uncompromising standard. His book, Unit Satyajit, remains a vital photographic memoir of this era, capturing the discipline of a master who sought excellence in every frame.

Yet, while Ray’s influence sharpened Poddar’s sense of composition, it may also have nudged his paintings towards a cinematic framing that favours atmosphere over structural tension. However, unlike Ray’s frames, which are anchored in narrative progression, Poddar’s canvases often resist closure, hovering instead in a suspended emotional moment. This can be deeply evocative, but it also means that storytelling in his visual art remains impressionistic rather than architectonic — more mood than sequence, more lyric than plot. For some viewers, this very ambiguity may be the strength of his work; for others, it could raise questions about whether the discipline of cinema ever fully translated into the rigour of pictorial construction.

A DIALOGUE OF MEDIUMS: THE TECHNICAL SYNTHESIS

Poddar is a restless experimenter, refusing to be bound by a single tool.

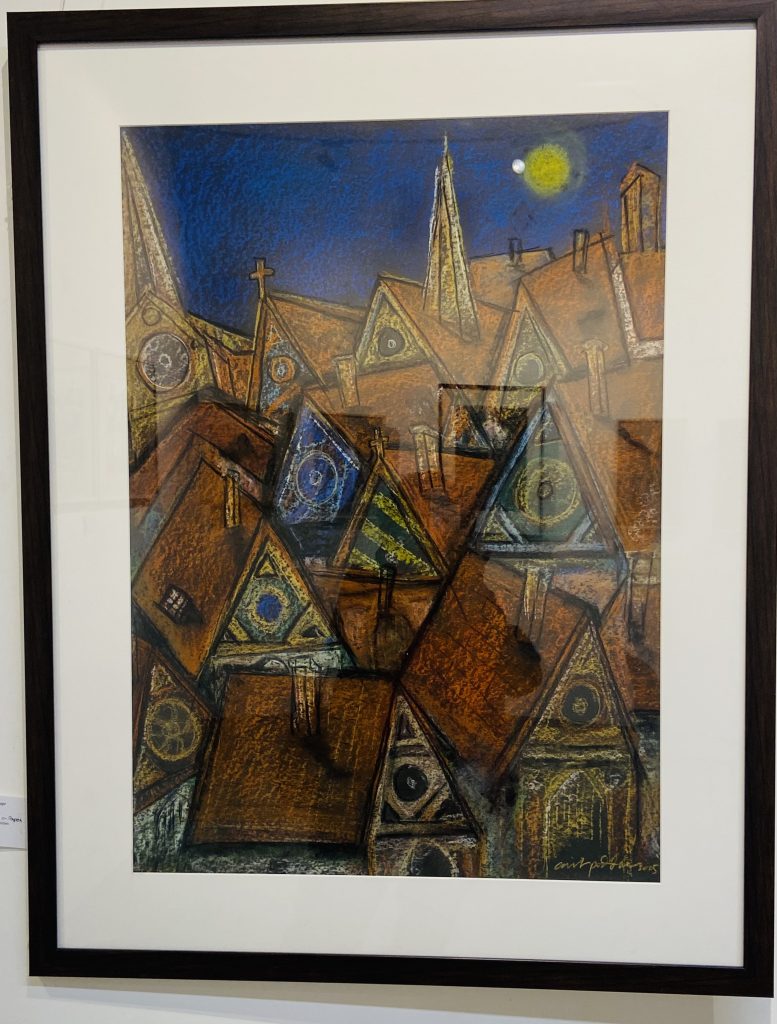

Though he uses Sumi ink, his technique departs from traditional Japanese calligraphy. While the Japanese masters focus on the fluid “one-stroke” philosophy, Poddar uses the ink’s deep, carbon-rich blacks to provide a structural skeleton for his European subjects, often layering it with Western perspectives.

In his Benares and Venice series, he uses watercolour to capture the translucency of light on water. When he seeks more tactile, visceral textures, he turns to pastels and acrylics, allowing him to build the “nervous,” raw energy he admires in the works of Egon Schiele and the decorative richness of Gustav Klimt.

Much like his favourite, Ram Kumar, Poddar uses these varied mediums to strip a landscape down to its emotional essence. Whether it is the grit of a Kolkata alley or the elegance of a Viennese square, the medium is chosen to match the mood of the memory.

Poddar’s refusal to settle into a single stylistic signature has earned him admiration as well as quiet scepticism within curatorial circles. While his versatility across ink, watercolour, pastel and acrylic reflects a genuinely exploratory temperament, it can be argued that this very multiplicity risks blurring the distinctiveness of his artistic identity. In an art world that increasingly values conceptual consistency, Poddar’s practice can appear defiantly old-fashioned — driven more by visual pleasure and travel-induced inspiration than by a sustained aesthetic inquiry.

While Poddar often speaks of Japanese ink philosophy as meditative and restrained, his own application of Sumi ink is far from austere. Instead of embracing the radical minimalism of Japanese brush traditions, he tends to load the surface with layered textures and tonal contrasts. This could be read as a conscious resistance to emptiness — a refusal to relinquish emotional density in favour of spiritual quietude. In this sense, his work does not so much adopt Japanese aesthetics as absorb them into a fundamentally expressionist temperament rooted in Bengal’s visual culture.

BEYOND SIGHT: THE CHILDREN’S GUERNICA AND THE QUEST FOR PEACE

Perhaps the most profound chapter of Poddar’s career is his commitment to the Children’s Guernica project. Initiated during the centenary of Benode Behari Mukherjee—the “national treasure” artist (in Poddar’s words) who continued to create after going blind—Poddar’s work with the project is a crusade for dignity.

By leading workshops for disabled and visually impaired children to create massive peace murals, he echoes the anti-war sentiment of Picasso’s original masterpiece. For Poddar, it this not merely an expression of empathy, it is a philosophical statement. He believes that because art is an “expression of the soul,” the loss of physical sight does not diminish the power of vision. Through these murals, he gives a voice to the marginalised, transforming their quest for peace into a vibrant, public reality.

THE PERPETUAL TRAVELLER — AND THE QUESTION OF ABSENCE

Today, based in Kolkata but always packed for the next destination, Asit Poddar remains a bridge-builder. He is an artist who has survived the fractures of history to create a world where a village in Bengal, a street in Vienna, and a temple in Benares all exist on the same plane of aesthetics.

There is also a persistent nostalgia that courses through Poddar’s landscapes — a longing for vanishing streets, riverbanks and older civilisational calm. While this lends his work a gentle melancholy, political conflict and social rupture rarely enter his pictorial frame. The violence of history seems to dissolve into lyric remembrance. Whether this reflects healing, aesthetic choice or quiet withdrawal from harsher realities remains open to interpretation.

Though Poddar has lived and worked in India for decades, much of his recent visual imagination continues to be stirred by European streets and Japanese ink traditions. While these journeys have clearly enriched his formal language, they also raise a quiet question about absence — about the India that remains largely outside his frame except as memory or metaphor. At a time when many artists are engaging directly with the textures and tensions of contemporary Indian life, Poddar seems to turn instead to older, gentler geographies.