INDESTRUCTIBLE: Close to 26,000 tonnes of plastic waste is generated across India every day, of which more than 10,000 tonnes stays uncollected. It takes thousand years for pet bottles and other plastic products to decompose

By Amitabh Sinha

In five minutes, around the time it takes to read this piece, around five million plastic bottles will be bought around the world, many of those in India. With PM Modi calling for an end to single-use plastic, THE INDIAN EXPRESS examines the scale of the problem. But first off, what is single-use plastic?

FOR the last few weeks, Ashish Jain has been getting four-five calls every day from plastic manufacturers across the country asking what was likely to happen on October 2. As director of the Delhi-based Indian Pollution Control Association (IPCA), a research firm that works on waste management and air pollution, the 41-year-old Jain has been involved in stake-holder consultations on the impending crackdown on plastics. And though the government has clarified that it was not going to impose a blanket ban on single-use plastics from October 2, Jain says the apprehensions have remained.

“Manufacturers of general-use plastics like carry bags are complaining that they are not receiving orders, with traders anticipating the announcement of a ban on October 2. This is their peak season, ahead of festivals such as Diwali, but, apparently, even normal orders have been put on hold,” says Jain.

It all started with PM Narendra Modi, who, in his Independence day speech, gave a call to get rid the country of single-use plastics. Some subsequent statements, from Modi and his ministers, have made it clear that a crackdown on plastic would be to this government’s second term what Swachh Bharat campaign was to the first.

However, Swachh Bharat — at least in its attempt to make India open-defecation free — has been a relatively straight-forward task, even if quite humongous. The move to get rid of plastic waste, on the other hand, is a vastly complicated and multi-layered problem. Plastic is so deeply entrenched in our lifestyles, and therefore in our economy, that any move to ban it wouldn’t be without major disruptions. A complete ban on plastic is not just unrealistic, but almost impossible. The attempts by various states governments to ban some plastic products, like carry bags, have also remained largely ineffective.

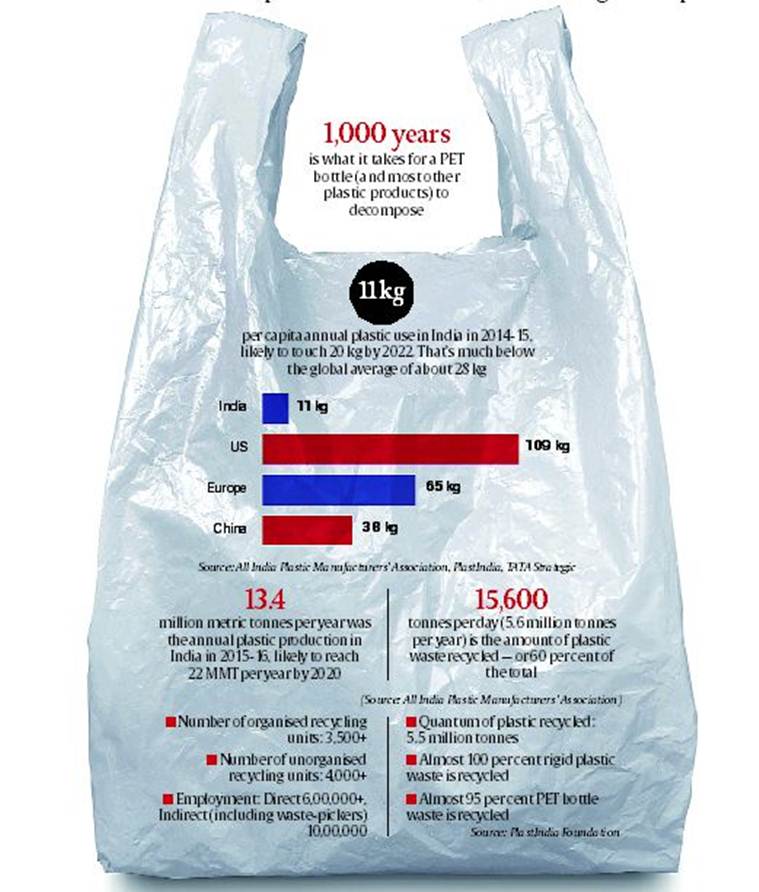

Yet, there’s no doubt that the plastic problem is a growing one. Close to 26,000 tonnes of plastic waste is generated across India every day, of which more than 10,000 tonnes stays uncollected. With most plastic products taking close to 1,000 years to decompose, these remain scattered in our surroundings. In fact, one of the main reasons for repeated flooding in Mumbai is plastic choking up sewage networks.

Defining single-use

The problem starts with the definition itself. There is no clear definition of what is single-use plastic. It is generally understood to mean all packaging products, carry bags, bottled drinks, straws, containers, decoration plastics, cutlery — anything that you would ordinarily throw away after one use.

A committee under the Environment Ministry is working on finalising an unambiguous definition of single-use plastic. A senior government functionary told The Sunday Express that a notification in this regard could be expected by October end. The notification, he said, was also likely to spell out the red-lines for the plastic industry.

Swaminathan Sivaram, a former director of the Pune-based National Chemical Laboratory and a member of an expert panel constituted by the Department of Petrochemicals to categorise single-use plastic, says any product whose life cycle is less than a few hours should be classified as single-use. Such plastics are being targeted as these are the ones that end up in the bin in large numbers.

The crackdown

Experts say that in all likelihood, the government is not expected to announce the kind of general ban that many states have put in place. Instead, it seems to be preparing for a more layered approach to deal with plastic waste, one that involves a time-bound phase-out of some products, strengthening of waste management practices, incentives for creating high-quality recycling infrastructure, and mandatory blending of recycled material in plastic.

“A blanket ban on single-use plastic would be counter-productive… Plastic is essentially a waste management problem. We do not have systems in place for effective segregation, collection and recycling. Once we ensure this, a majority of the problem is taken care of,” said former Environment Minister Jairam Ramesh.

“This is not to suggest that nothing needs to be done on plastic waste. There are many eco-sensitive areas where the amount of plastic waste has reached saturation point. So, in places such as the Himalayas, for example, a ban could be justified. There is utility in many single-use plastics. So we need to consider these moves with caution. There are lakhs of livelihoods at stake,” he said.

As of now, the government is learnt to be working on a list of products that can be categorised as single-use plastic. Out of 64 products initially suggested, 12 are learnt to have been finally included. It is expected that the government will announce a phase-out of, or even an immediate ban on, these 12 items on October 2. These items include carry bags, cutlery like spoons, glasses and plates, straw, bottles with volume less than 200ml, thermocol, and plastic used in decoration. Even the white woven carry bags that look like cloth and are sometimes used as a replacement for plastic bags is learnt to be on this list. These bags are produced by blending cotton with plastic, and thus are non-recyclable.

“Unavoidable plastic use will continue. Avoidable plastic use will be discouraged,” the government functionary said.

Reduce, reuse, recycle

The bigger challenge is to put in place an efficient waste management system, which would bring in a more sustainable way to deal with plastic waste. This would involve segregation of waste at source, collection and recycling. It would also mean nudging people towards making behavioural changes.

Almost 60% of all plastic waste in the country is recycled. But most of it is done in informal, home-based industries which produce very low-quality recycled plastic.

It is possible for recycled plastic to be mixed with virgin material to then produce high-grade plastic products that are required to store food, for example, but that requires a more organised industrial scale set-up equipped with modern technology. A PET bottle, when currently recycled, most likely ends up producing cloth-like fibres that are used to make shirts or jackets. But a PET bottle can be recycled into an equivalent grade of plastic to produce another PET bottle, thus reducing the demand for virgin plastic.

But high-quality recycling has its own requirements. The input material has to be unadulterated. Dirt or mud on the plastic can make it unsuitable for high-quality recycling. That means users would need to clean the plastic bag or packaging material before disposing it in garbage. Similarly, multi-layered plastic, the kind that is used for packaging branded chips or biscuits, for example, are difficult to recycle because of the presence of materials that are chemically different.

The economics of recycling

The recycling industry depends heavily on rag pickers and waste collectors. Right now, almost all the plastic waste they collect has a price, ranging from 3-4 a kg to 30-40 a kg. PET bottles, for instance, can fetch them 15-20 a kg. A high-quality bucket made of virgin plastic can fetch upwards of 30 a kg. These are easier to collect and have substantial weight, so the collector gets a higher price for fewer number of items collected. Articles such as wrappers of chocolate and sweets, straws and shampoo sachets, however, are often left out. These are priced at3-`4 a kg, and many more need to be collected. And these small plastic items are also the ones that are littered the most.

An important element in this is what is known as Extended Producer Responsibility, or EPR, that makes it mandatory for the producing company to get their used products collected. In India, EPR guidelines for plastics were introduced for the first time in 2016, in the Plastic Waste Management Rules. Such EPR arrangements have existed for lead acid batteries since 2000 and for e-waste since 2011. So far, the implementation of EPR guidelines on plastic has remained sluggish. But that could be changing now.

“Many companies have started following EPR guidelines after the (PM’s) August 15 announcement. So far, about 150 major plastic producers are complying to the guidelines, collecting nearly 30% of their total plastic sales,” says Jain of the Delhi-based IPCA.

But plastic cannot be recycled indefinitely. The purest of them can undergo not more than 7-8 recycles. They would need to be utilised somewhere else after that. In recent times, plastic waste has found good application in road construction. Additionally, plastic can be converted to industry level gasoline as well.

But those are end-of-life solutions. As of now, the idea seems to be to put in place systems to ensure that the unnecessary use of plastics is minimised, a task which involves the coming together of government, industry and the public.

WAR ON PLASTIC: HERE’S THE BIG PICTURE

Prime Minister Narendra Modi underlined the importance of shunning single-use plastic both in his latest Mann Ki Baat radio broadcast and in his address to the nation on Independence Day. The PM invoked Gandhi in his appeals, and it has been speculated that a specific ban may be announced on October 2, the Mahatma’s 150th birthday.

Single-use plastic

As the name suggests, single-use plastics (SUPs) are those that are discarded after one-time use. Besides the ubiquitous plastic bags, SUPs include water and flavoured/aerated drinks bottles, takeaway food containers, disposable cutlery, straws, and stirrers, processed food packets and wrappers, cotton bud sticks, etc. Of these, foamed products such as cutlery, plates, and cups are considered the most lethal to the environment.

Impact on environment

If not recycled, plastic can take a thousand years to decompose, according to UN Environment, the United Nations Environment Programme. At landfills, it disintegrates into small fragments and leaches carcinogenic metals into groundwater. Plastic is highly inflammable — a reason why landfills are frequently ablaze, releasing toxic gases into the environment. It floats on the sea surface and ends up clogging airways of marine animals.

Plastic waste management

The Plastic Waste Management Rules, 2016 notified by the Centre called for a ban on “non-recyclable and multi-layered” packaging by March 2018, and a ban on carry bags of thickness less than 50 microns (which is about the thickness of a strand of human hair). The Rules were amended in 2018, with changes that activists say favoured the plastic industry and allowed manufacturers an escape route. The 2016 Rules did not mention SUPs.

On World Environment Day in 2018, India pledged to phase out SUPs by 2022. The PM has called for “a new revolution against plastic”, and some government-controlled bodies such as Air India and the Indian Railways have announced they would stop SUPs.

Size of the problem

There is no comprehensive data on the volume of the total plastic waste in the country. A 2015 study by the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) surveyed 60 cities and extrapolated the data to estimate that the country generated around 26,000 tonnes of plastic waste daily in 2011-12, equivalent to the weight of 4,700 elephants.

About 70% of the plastic waste was collected; 60% was recycled. It is likely that the actual daily generation of plastic waste is much more. According to the Plastic Waste Management Rules, all states and UTs are required to send annual data to the CPCB; however, many states and UTs have failed to comply.

Recycling of waste

About 94% of plastics are recyclable. India recycles about 60%; the rest goes to landfills, the sea, and waste-to-energy plants. Most experts view recycling as an interim measure until plastic is completely banned. “Plastics have an end life too. They can’t be treated more than four-five times,” says Dinesh Raj Bandela, deputy programme manager (plastics) at the Centre for Science and Environment. The CPCB warns that recycled products are at times more harmful to the environment, as they contain additives and colours.

Models before India

At least 60 countries around the world have fully or partially restricted the use of non-biodegradable polymers. Consumption has reduced in at least 30% of the countries, while 20% have failed to achieve the goals, says a 2018 report by UN Environment.

In 2002, Ireland imposed a 0.15-euro levy, Plas Tax, on plastic bags. A dramatic change in behaviour was seen within a few weeks. In 2008, Rwanda imposed a blanket ban on the sale, use, and production of plastic bags. A wave of illegal imports from neighbouring countries followed, and Rwanda was forced to increase penalties. After initial hiccups, residents switched to green alternatives.

A 2011 study by the Delhi School of Economics suggested that levying a fee on consumers would yield better results than a ban, due to “little enforcement capacity”. People may be forced to carry biodegradable bags to grocery stores, vegetable markets and shopping malls if the alternative were to hurt their pockets.

For multi-layered packaging, experts have suggested effective buyback schemes and recycling units. The Prime Minister has mentioned the use of plastics in road construction and extraction of fuel. However, these initiatives would require capital investments and commitment.

Courtesy: Indian Express