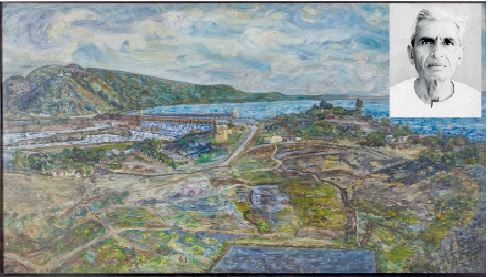

Panoramic view of the Tungabhadra dam ( inset) Rumale Chennabasaviah

By Prema Viswanathan

“What would life be if we had no courage to attempt anything?”

–Vincent Van Gogh

COURAGE was an attribute Rumale Chennabasaviah held sacred in art as much as in life. Like the celebrated Dutch artist Vincent Van Gogh with whom he is often compared, the freedom fighter and painter of flowers and foliage, whose 112th birth anniversary falls on September 10, was a gentle rebel, using colour to express emotion at a time when most landscape artists adhered to a realistic and representational style.

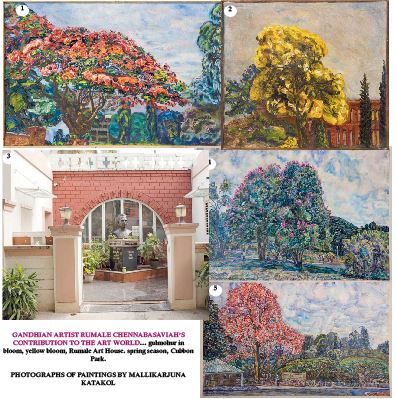

Although he imbibed the basic principles of painting at Kalamandira in Bengaluru and in Chamarajendra Technical Institute in Mysuru, Rumale was a rule-breaker. As eminent artist KG Subramanyan said, “Most of his water colours have a striking originality and freshness that one cannot miss.” Whether it is the flaming gulmohur or the golden laburnum, Rumale’s brush with art was awash with intensity, imbuing these objects of nature with a personality of their own.

Rumale’s foster son, Sanjay Kabe, who used to accompany the artist during his painting expeditions to Bengaluru’s Cubbon Park and Lal Bagh when he was a child, recalls his exuberance and perfectionism. “I have accompanied him from the 1960s until the late 1980s and found that his commitment only increased with time. I remember the meticulous preparations he made before painting. He would first go and study the subject and pick the spot for painting based on perspective, light and shade. Once that was done, he would spend time selecting the right colours, brushes, knife, oil, palette and canvas, and pack them in his khaki bag, along with a small, foldable stool. My sister Shabala and I would accompany him in an autorickshaw to one of the parks or other locations. He would sit on the stool and arrange his painting materials. When he was happy with the light and shade conditions, he would commence his work….”

KARMA YOGI

KABE provides yet another example of the commitment which was a hallmark of Rumale’s personality. “He travelled several hundred kilometres in a state transport bus to paint the series on the river Kaveri or capture the landscapes which would be submerged under the dam project. He would walk tens of kilometres to the site at the age of 70 years plus. ”

For Rumale, these adventures were an integral part of the life of a karma yogi – a role he saw himself in. He shared with his young foster son the example of the British artist JMW Turner tying himself to a ship’s mast to experience the storm which he would later paint. However, while he held the Western masters in high regard, Rumale was not awed by them, says Kabe. In his curatorial volume ‘Varna Mythri’ for the retrospective to commemorate the birth centenary of Rumale at the National Gallery of Modern Art in Bangalore, art critic Srinivasa Murthy writes, “While painting the Narasimha Swamy temple across the Malaprabha river, during the crossing, he nearly got washed away in flash floods. Fortunately, he held on to the painting.”

The landscape art tradition that Rumale inherited was dominated by painters for whom art was merely a celebration of imperial might or a way to mirror the beauty of nature. Rumale broke away from that tradition. His was not a realistic depiction of nature in the manner of other landscape artists nor was it ‘a visual conquest,’ a term art historian Shukla Sawant uses to describe the works of British artists who painted Indian landscapes and monuments during the colonial era.

ROMANTIC MODERNIST

RUMALE was a romantic modernist and an inadvertent ecological crusader and archivist, capturing for posterity both the state’s horticultural wealth as well as its disappearing monuments which would fall prey to urbanization and predatory development. In addition to this, like his celebrated precursor Van Gogh, he would infuse into his study of flora a vibrancy and personality one usually associates with human beings.

At the same time, what one sees in Rumale’s works is no pristine, untouched manifestation of nature, points out Sawant. The landscape that Rumale, and Venkatappa before him, were painting, had ironically, been transformed by German and Australian horticulturists who were bringing a plethora of flowering plants and trees to Karnataka. These botanical interventions resulted in Lal Bagh in Bengaluru and the Botanical Gardens in Mysuru that Rumale celebrated through his art.

Rumale was a ‘gestural’ artist, much like Ramkinker Baij, the iconic artist of Shantiniketan, says Sawant. He was very much a modernist in the bold way in which he used colours to express feelings and moods, slapping on paint in a spontaneous fashion, rather than applying it carefully as a representational painter would do. However, it must be stressed that Rumale did not profess allegiance to any formal school of painting, including the Gestural School of New York. The similarities, if any, were coincidental. As his oeuvre evolved, his work took on more and more of an abstractionist patina.

Rumale used the medium of water colour in ways that hardly any painter – Western or Indian – had done before, making large sized works and also slapping on paint on the canvas to create an illusion of opaqueness usually only seen in an oil painting.

He was able to get these effects partly because of his insistence on quality and quest for perfection.

HE IS UNIQUE

SAYS renowned artist SG Vasudev, “Rumale’s contribution to art is exemplary. He used only imported (Windsor and Newton) water and oil colours and was a stickler for quality and perfection. No one in his generation has handled the medium so well. In that respect, he is unique.”

Vasudev points to the fact that Rumale came late into the world of art – at the ripe age of 52. This happened because the early years of his life were devoted to campaigning against colonial rule, courting arrest, participating in the Salt Satyagraha and serving the public as a member of the Sewa Dal, a grassroots organization of the Indian National Congress, following the path outlined by his political mentor, Mahatma Gandhi. It was only in 1962 that he took up painting, bringing to his art practice the same zeal and passion that he had poured into his political pursuits. As he writes: “A true artist has to go through the litmus test of the Independence Movement. If I can do that, my art and writings will turn out to be more vital.”