Goa is abuzz with excitement as vintage bike and car owners, users, collectors and fans are decking […]

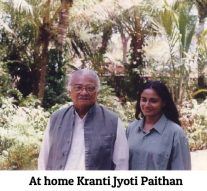

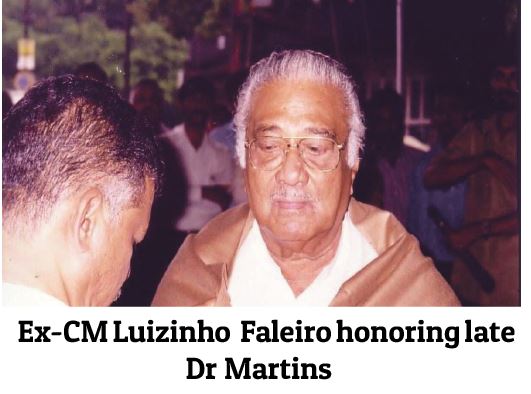

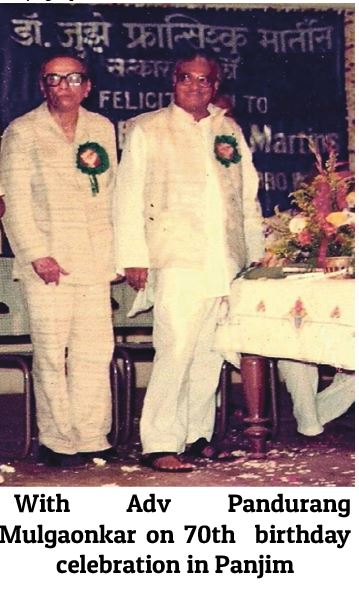

MY FATHER’S GIRL!By Meenacshi Martins

Aug 16- Aug 22, 2025, Tribute August 15, 2025An emotional tribute to the late Dr Francisco Martins by his ever grateful daughter…

WHEN one experiences a personality as huge as was my father’s, from close quarters, through thick and thin, for better or for worse, it becomes difficult to find words to express the feeling, each thought unfolding a panorama of memories as vivid and as colourful as was his life

Dr Jose Francisco Xavier Antonio Martins, was my father, before he was anything else. To me at least

To others he was a living legend-an educationist linguist, writer, thinker, fighter for Goa’s Liberation and later Goa’s identity. Of course, a physician with a magic touch that healed many and shaped several lives.

He was a designer of my destiny, beginning with the name he along with my mother, Dr Esmina Martins, chose for me, he defined the way my life would go. “Meenacshi” — daughter of Kubera (god of riches and treasure), the goddess of Madurai and wife of Siva. A name that gave my life, my character and my future, a meaning. It was a rare and a bold move against the trend in the times of colonial rule, but my parents, staunch believers of Indian philosophy, stuck to their beliefs despite the objections of the Church and thankfully. I remained Meenacshi.

Turbulent times marked my childhood, set auspiciously during the last lap in the freedom struggle of Goa. Bountiful military personnel and fearless freedom fighters were part of my growing up and patriotism, my staple diet. Like most daughters, I was my father’s girl, his dream come true and his hope. And in return he fascinated me. While he negotiated for separate identity for Goa, in Delhi I would miss him, clinging onto his pillow, for it smelt of him. Pacifying me he said, “1 will take you everywhere when you grow up. That day came too soon when he made me stand by his side to hand him the pages of his poem as he recited proudly and elegantly. “Shrivaddo gaon amcho. Lhan, sundor, apurbajecho”.

It was the 4th centenary celebration of the Salvador do Mundo Church. And I was five years old. Same month he left for Delhi and took us along. And I remember performing “Sare jahan se accha…” at the Rajya Sabha where Puruxottam Kadodkar had taken us, properly draped in a sari and all.

PROUD OF COUNTRY’ CULTURE

HE believed I deserved austere education and appointed a local master to initiate me in the philosophy and culture of the country he was so proud to be a part of, I was taught epics, Mahabharata and Ramayan from a very early age. Adding a little later Bakibab Borkar’s “Gitai” with some Eklavya. Birbal. Tarzan comics and a Chandoba thrown in for the child in me. All this while other children my age did what, I did not know.

He had a vision and a philosophy few in his era could comprehend, and foresightedness, which he downloaded on me. For a man who refused to kneel down in Church and bow before a system he had difficulty in believing, he was not afraid to freely express exasperation at blind faith in Church and its doings. He refused to participate in its religious activities and encouraged me likewise. “God is everywhere,” he told me. “You need not go to Church.” With that one sentence he set me free from the shackles of restricted thinking and a forced belief system. Encouraging open-mindedness so needed to have larger perspectives and attributes of over-all acceptance.

A man with simple tastes and a simplistic living, my father possessed only three sets of clothing at a time. His trade mark white kurta-pajama. My mother too, influenced by him, wore nothing but cotton saris, sometimes priced ridiculously at Rs9 and bought at the fair price shop in the Mapuça market. As a girl I wore khadi dresses. Frustrated and upset, the teenager in me would revolt several times only to get a lecture from my parents on frugality for self while being selfless for others. Never understood all that till very recently! Their conscience is what my wardrobe is made up of today, simple cottons and handlooms.

He was a man with a mind as large as the horizon and a faith in his daughter which he lavishly expressed the day he opened his book shelves for my use. A collection that was worth its weight in pure gold. Books he had collected before and during his prison term at Aguada Jail which included Plato, Shakespeare. Yogabhashya, Upanishads. Kannufru to Atre’s Marathi plays along with several dictionaries remained stacked side by side on the top shelves while an entire lower shelf was piled with amongst others DH Laurence’s “Lady Chatterley’s Lover.” Emile Zola’s novels, Saul Bellow’s “Herzog” and Daphne du Maurier’s “Rebecca” which became my all time favourites.

CENSORED BOOKS!

ONE day my mother had a showdown on the choice of books I was found with. “I trust her to make good use of what is in them.” My father calmly explained why his daughter was allowed access to the books, censored and covered in brown paper then by the Church.

Books, gardening and fishing, I guess were his major passions. His evenings were spent in the warmth of the setting sun in the small river amongst our fields where he taught me to swim even before I could walk independently. Later, he would seat me in the boot of our Renault car while he collected fish from his vast sprawling nets. I remember the glitter of jumping prawns in the twilight on a full moon night. His “cantolli” (fishing nets) were his prize possessions. Every single night I would wait for him for dinner when “shoutaio, khorchandeo, kaunduran, thigur” and a conni full of prawns would be poured on the kitchen floor for my pick.

All the fun came to a stunning halt when my mother had her first heart attack, a near fatal one. And perhaps it was the first terrifying experience of mine to see my father lost and fearful. I have seen him standing on the threshold of Ward 14 and staring at where my mother lay, “just making sure that she is still there” he would say; I knew life was drained out of him. But he stood tall despite the pain and anguish.

It must have been truly difficult, for he started to drink and smoke rather heavily. One day I revolted and threw a perfect fit. I threatened him saying that I would stop studying if he with immediate effect did not stop smoking. I was 12 then and did not have any idea of the impact of my statement. The credit goes to the innate strength and integrity that my father possessed and which I am exceptionally proud of, for he stopped smoking the very next day. A few days later, just before his birthday on the August 12, he suddenly stopped drinking

Even at weddings be would hand over the glass of wine after he had raised a toast with out as much as a sip. And my heart would swell with pride. “My father does not drink.” I would declare to the bewildered hosts.

His will power is what legends are made of. He stood for liberation and an independent identity for Goa while many believed otherwise. He refused to accept an offer of freedom by the Portuguese rulers in exchange for a written statement of apology and he went to prison leaving his ailing father and aged mother and grandmother to fend for themselves, based solely on his conviction and beliefs. He underwent a surgery without anaesthesia. Named his children Sanskrit names even while Goa reeled under the colonial rule put us in Marathi medium local schools, to understand the community better.

My father supported and paid for the education of several children even while he barely managed to run his own household. He walked his talk and put the adage of greater good for the greatest number of people to its best use. Two years prior to his passing, when he came to live with my family, I was given the gift of childhood all over again. Following him around his lavish garden remained my favourite activity. I could talk and talk all the time telling him practically everything that happened in my life in gross and boring detail. And how easy it was to fall back on childhood routine I found out as I kept asking him for words and meanings. As a child, I called him my walking talking dictionary. Fed up, one day he had asked me to use a real one and I had retorted “Why should I, when you are there!” He was fluent in several languages, be it Latin, Portuguese, French, Hindi, Marathi, Konkani and English, and he was learning Sanskrit. By logic he must have figured that the dictionary was one book I could be allowed to read even at the dinner table.

In my house a return gift awaited him, my own book collection. And he read from practically six in the morning to near midnight or till his eyes tired and he could not read any more. I marvelled at his ability to grasp new technology with the eagerness of a child. He read my son’s Harry Potter series with a grin on his face and watched “Lagaan” with us with an unparalleled fascination. He was a lover of the game. My father gave me the most memorable of moments, moments I shall cherish and hold for posterity. The time he attended one of my workshops on “self-healing” and lifestyle management was one of the most touching experiences. Following which he went on a diet, exercised and meditated. It was as if life had come a full circle. The man I considered as the most well read, most intelligent, was learning from me, at the age of 82!

He patiently sat by my side as I studied. The Upanishad interested him and we read theories on life, death and after life. “I am grateful,” he said later, “I would have never known this knowledge existed.” I am grateful too, for the sheer humility and the pleasure of having been able to do so.

WE WERE SOULMATES

HE held within him a century worth of knowledge. And I am lucky to be a recipient of some of it. We were soul mates, partners in knowledge. And that perhaps shall remain the only significant gift we shared. This was my father. A man who lit up my life with Aladdin lamps, the dawn I decided to visit this planet, two months before schedule and a man who had continued to light up my life thereon. For what I am today is based on what he taught me when I was little, genetic influences notwithstanding.

I do not believe in death and therefore, I am lucky to have my father live on in my life. In my hands, as I heal, treat, plant, re-pot and graft, in my heart, as I stand up for justice; in my thoughts as I write and in spirit when I need strength. I know he lives on in public memory too and in the collective consciousness of Goa’s history despite it being 21 years since his demise. He would have been 105 years old today.