Goa is abuzz with excitement as vintage bike and car owners, users, collectors and fans are decking […]

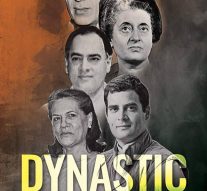

RAJIV GANDHI, SCRIPTED A NEW INDIA

Uncategorized October 31, 2025Looking back, looking forward with books which have something to say in the annuls of governance which shape the past, present and future of a country…to understand how one political party has defined India, it is useful to catch up with senior journalist Kedar Nath Sharma’s insightful book “Dynastic Ambition.” Goan Observer takes pleasure in carrying an excerpt from “Dynastic Ambition, Legacy of the Nehru-Gandhi’s to India’s Democracy” by Kedar Nath Sharma…

BREAKING from the quasi-socialist policies of his grandfather and mother, which had hobbled trade, industry and the whole spectrum of the economy for decades, Rajiv Gandhi gave a radical head start to economic liberalization. Part by part he began dismantling the notorious `Licence-Permit-Quota Raj’, introduced by Nehru and institutionalized by Indira Gandhi. A new industrial policy, announced by him in 1988, was a major watershed in India’s political management of the economy. To a large extent it modified the Nehruvian-era Industries (Development and Regulation) Act of 1956 which had made the public sector the commanding height of the economy and regulated the growth of the private sector. Most people in the government and outside knew that the public industries were a white elephant and a drag on the public exchequer. Year after year the government had been making budgetary provisions to subsidize their losses. Yet no serious efforts had been made to shift the emphasis from the public sector to private enterprise, simply because the Congress equated the support for public sector with patriotism. Rajiv Gandhi changed this long held policy line. Addressing a Congress workers rally in Madras (now Chennai) in December 1987, he asked: “Can we afford a socialism where the public sector, instead of generating wealth for the people, is robbing and sucking up the wealth of the people?”

Liberalizing the Economy

The thrust of Rajiv’s economic reform was to life the blinds of regulations to encourage entrepreneurship and to open the economy for investment and collaboration and import of foreign technology. The measures adopted by him to achieve these objectives included doing away with some antiquated licensing procedures and fixation of quotas, reducing or eliminating duties on technology imports to encourage Indian companies to modernize their production process and allowing them to manufacture as much as they could. Rajiv’s reforms also aimed at simplifying and rationalizing tax laws and ‘broadbanding’ of industries (the latter allowed passenger car manufacturers to produce trucks and truck manufacturers to make cars.) Indian companies were also allowed to tie-up with international firms o improve their performance in local and international markets. The measures initiated by Rajiv served as catalysts for more ambitious economic reforms, launched by P.V. Narasimha Rao in 1991.

Rajiv had made it clear to loss-making public sector companies that if they failed to turn into the black within a specified time he would not hesitate to sell them off to private owners or close them down. This sort of threat was unthinkable during Jawaharlal’s or Indira Gandhi’s time. Rajiv was not enamored of the virtues of socialist society or its child the public sector. He carried no ideological baggage, nor did his advisors who came from upper class backgrounds had a natural inclination towards the free enterprise. They were more open to the West, particularly the United States.

Rajiv was convinced that his grandfather’s state-controlled, ideology-laden socialist economic policies, further strengthened by his mother, had outlived its purpose, and it was the time to integrate the Indian economy into the global one to catch up with the developed world. But he shied away from making radical departures, as the Congress party, long wedded to Nehruvian economic philosophy had to be persuaded. This made him move slowly. Nevertheless, the first steps that he had taken had m tremendous impact. The liberalization move ushered in significant changes in telecommunications, airlines, defense and the home appliances sectors, and encouraged Indian companies to modernize their production processes.

Rajiv’s economic policies parked a consumer boom, triggering a surge in domestic production of television sets, cars, scooters, kitchen appliances and computers. In 1984-85, sale of cars, previously owned by the privilege few, rose by 52 percent, scooter and motorbike sales grew by 25 per cent. Almost every day new businesses, restaurants and shopping complexes opened. The housing and real estate markets saw unprecedented boom. Stock markets grew by 400 per cent. Between 1985 and 1990, exports had tripled to Rs32,25 core, industrial output grew by 59 per cent and the number of capital issues increased by 133 per cent. By 1990, mega-issues, exceeding Rs500 crore, from companies like Reliance, Larsen &Toubro and Tata Iron and Steel Company had become commonplace. It was during this period that Reliance Industries saw spectacular growth and its founder, Dhirubhai Ambani, who was once a petrol pump attendant in Aden, rose to become one of India’s top industrialists. The reforms showed that once liberated from the yoke of state controls the Indian economy could grow as fast as any developed economy in the world.

Between 1984 and 1989 the Gross National Product (GNP) grew at close to six per cent a year, double the average of three per cent during Indira Gandhi’s 15-year rule. Industrial production grew at a compound rate of over 12 per cent a year and in 1988 foreign investment had reached Rs2,397 crore. The main areas of foreign collaborations were electrical equipment, industrial machinery, transportation, telecommunications, machine-tools, household equipment and drugs and pharmaceuticals industries. There was also a significant increase in agricultural production reaching 180 million tonnes in 1987-90, nearly 35 per cent higher than that under Ms Gandhi’s tenure.

The partial liberalization of the economy couuled with a limited opening of doors to foreign investment in cetain scectors, attracted international interest in the Indian market for the forst time since Independence. Between 1985 and 1987, the Rajiv government approved 2,834 foreign collaborations with Indian companies , worth Rs342 core. ?The New York Times reported tht US$2.3 billion in provateinvestment had been added to steel, cement, fertilizer engineering and other major industries in 1983-88. In addition, non-resident Indians (NRIs) invested over US$4 billion in dollar, 700 million in sterling and Rs11,000 core in rupee accounbts between 1985 and 1987. The United States topped the list of financial tie-ups, with 191 collaborations, followed by Federal Republic of Germany with 178, Japan, with 94, and the United Kingdom, with 47.

Commenting on Rajiv’s economic policies after his death Ratan Tata, chairman of the Tata Group, told The Economic Times: “The results of Rajiv ushering in an era of new economic policies are remarkable. I perceive a significant difference in our industry’s product quality over the last five or six years. There is no doubt that in manufacturing, process technology and product finish, we are closer to world-class products than we were in 1985.”

Rahul Bajaj, chairman of Bajaj Auto Limited, agreed with Tata: “…the change had come. Earlier, industrialists had to go to Delhi frequently for licenses but after Rajiv they didn’t have to, except in the case of those who wanted undue favors. Officials, too, changed their attitude. They were prepared to listen to the problems or demand f large houses. It is to Rajiv Gandhi that I give full credit for initiating the policies of liberalization and modernization. Before him, no politician of any standing had the guts to talk about it as they were all fed on the socialist rhetoric. Rajiv recognized instinctively that the economy had to grow.”

However, there were at least five major concerns arising from Rajiv’s policies on the macro-economic front: large budgetary deficit on account of revenue deficit, low rate of savings in the economy on account of increased public spending, a precarious balance of payment following increased imports, growing unemployment and rising external debt. In April 1988, the government put the figure of eternal debt t Rs55,000 crore, but the Washington-based Institute of International Finance, which monitors the real debts of borrowing countries, placed the amount as of the same date at us$57.6 BILLION (Rs75,000 crore at the prevailing exchange rate at that time). The big gap was due to the government not including the amount of short-term load, estimated at around US/46.7 billion with an interest payment ofUS$474 million by April 1990. The IIF estimated that in April 1990 India’s external debt would add up to US$66.3billion, or Rs100,000 crore. The government’s Economic Survey of 1988-89 claimed that India’s debt-service ratio stood at 24 per cent, well below the crisis mark of 30 per cent. But if short-term loans and funds borrowed from NRIs were included, “the ratio goes up to 33%, well above the danger mark”.

There was also another concern more serious than the macro-economic ones and which had the potential to disturb political and social stability. It was the sharp widening of the gulf between the rich and poor. While industrialists and the middle class were prospering from Rajiv’s policies, the poor remained deprived of the fruits of liberalization and languished in abject poverty. Several starvation deaths were reported from the tribal districts of Orissa, where villagers were forced to feed on tamarind seed and mango kernel as the monsoon had failed and crops destroyed by drought.

The prime minister was conscious of the deficiency of his policies. At the Bhubaneswar session of the All India Congress Committee (AICC) ON 20May 1991 Rajiv publicly admitted that he could not achieve much” in his first term. But if the Congress returned to power in the 1991 elections, he said “all economic controls would end”. The 1991 Congress (I) manifesto, written under his guidance, unequivocally vowed to free the economy from the yoke of suffocating bureaucratic controls. Had he won a second term he would have almost certainly privatized most of the public sector enterprises, prioritized rural sector development, encouraged foreign equity instead of foreign debt, deregulated industry and moved towards a freely convertible rupee.

According to industrialist Rahul Bajaj, “Rajiv could not carry his idea of liberalization and modernization to their logical conclusion. There was resistance from the old guards who felt it at variance with their populist ideas. He could therefore not move as fast as he wanted. But he was in favor of freeing the economy not for the benefit of businessmen, but for the country.”

Fortifying the Panchayati Raj

Rajiv’s reforms did not simply stop at economic liberalization. Conferring constitutional status on Panchayati Raj institutions was one of his key moves at devolving power to local bodies – usually described as the Third Tier of government. In 1989 Rajiv moved the 64th Constitution Amendment Bill in the Lok Sabha seeking to make panchayat elections mandatory every five years and define the powers and functions of Panchayati Raj institutions. It sailed through the Lok Sabha, but failed to pass the muster in the Rajya Sabha, where the Congress (I) lacked a two-thirds majority. P.V. Narasimha Rao, who came to power two years after Rajiv’s death, introduced some changes in the original bill and steered it to success through both Houses in 1992 and has been described as one of Rajiv’s enduring legacies.

The Act provides for a three-tier Panchayati Raj institution – Gram Sabha (village council), Block Samiti (committee) and Zila Parishad (district board) and vests powers in state legislature to define their powers and functions. The state legislatures are required to provide grants-in-aid from the Consolidated Fund of the state and authorize panchayats to levy local taxes. The Act provides for the establishment of a finance commission every five years to eview the financial position of panchayats and make recommendations for the distribution of funds. The Act provides for direct elections at all levels of panchayati bodies, and sets the term of office for elected representatives at five years. It also provides for reservation of seats for scheduled castes/scheduled tribes and not less than one third of seats for women .

Rajiv Gandhi had two objectives behind pursuing the panchayat plan: (a) to involve village people in planning and implementation of development projects, and (b) to reinvigorate the sagging Congress organization at the grassroots. Rajiv was convinced that a village-level democratic infrastructure was a compelling economic and political necessity for a vibrant democracy. He sought to devolve power to elected village councils to enable them to function effectively as a basic forum of democracy with sufficient administrative and financial powers to decentralize governance. According to him the system of top-down planning, followed since independence was one of the major causes for the failure of development projects, besides bureaucratic corruption. In a memorable speech at an AICC session in November 1988 he had publicly acknowledged that that 85 per cent of funds allocated for anti-poverty programmes “did not reach the poor and were eaten away by middlemen who are not poor.”

Strengthening Defence

Rajiv Gandhi was keen on the modernization of defence infrastructure and services. It was meant to project India’s prowess as a regional power in an era of rapid geopolitical changes. The humiliation of Pakistan in the 1971 Indo-Pak war and the creation of Bangladesh had tilted the strategic scenario in India’s favor with the world recognizing it as an important player in South Asia. But American policy continued to block the assertion of India’s regional status. Bilding on the foundations laid by his mother, — such as the explosion of a nuclear device in 1974 – Rajiv spearheaded plans to establish India as a major military power stretching from the foothills of the Himalayas to a large part of the Indian Ocean. He ordered the expansion of the Indian Navy towards gaining blue-water capability and establishment of RAPIDS (Reorganized Plains Infantry Division) and ARAMIDS (Reorganized Mountain Infantry Divisions in the army equipped with rapid deployment capacity. He also ordered the expansion and modernization of the air force.

The Indian Navy was considerably expanded with the lease of a nuclear-powered submarine from the Soviet Union and the purchase of a second aircraft carrier from the UK It was decided that the next aircraft carrier would be built in India with indigenous technology and resources with limited foreign collaboration. The air force was equipped with MKG -23s and MIG-29s.The army got 155-mm Howitzer guns from Swedish Bofors and started work on developing a fully indigenous main battle tank, the Arjun. Works on two short-range – Agni and Trishul —and an intermediate guided missile development programme were accelerated. Agni was successfully tested in 1988. These developments put India into the exclusive club of countries with nuclear capability along with the US, the UK, the Soviet Union, France, China and Israel. In 1985 and 1986 alone, as many as nine agreements to buy foreign weapon systems were signed. Three of them were with the UK, two each with the Soviet Union and France and one each with Sweden and Singapore.

The new acquisitions led to significant increases in the defence expenditure. In 1985-86 it rose by 3.94 per cent, in 1986-87 by a4.12 per cent, in 1987-88 defence spending accounted for 17 per cent of the total government budget; it came down to 15 per cent in 1988-89 and 14 per cent in 1989-90. But in absolute terms the rise was fromRs7,987 crore in 1985-86 to Rs12,000 crore in 1989-90.Withincreased spending on weapon systems it was reported that the military faced a resource crunch in many crucial areas, like battlefield electronic countermeasures and jet trainers for the air force. Some analysts were reported to have said that after arms purchases there was barely enough money left for wages, transport, rations, maintenance and repayments of debts.

During 198 and 1988 the Indian Army, led by its chief, General Krishnaswamy Sundarji, asserted India’s military-strategic power in Sri Lanka to keep the peace between Tamil insurgents and the Sri Lankan armed force and in Maldives to rescue the regime from an attempted coup by a group of mercenaries. Both interventions were praised by major world powers, but denounced by neighbours – Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nepal. The Indian armed forces also held four code-named operations: Pawan in Sri Lanka, Brasstacks in Rajasthan deserts bordering Pakistan and Checkerboard and Falcon, close to the north-eastern border with China. At the same time, India continued its extensive military operations on the Siachen Glacier, 14,000-16,000 feet above sea level.

(Note: Journalist Kedar Nath Sharma completed his education from Allahabad and Lucknow universities and has worked with various publications – from The Times of India to Gulf Times, Reuters and Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU). He also wrote for Financial Times Energy, Business Middle East and Oxford Analytica.)