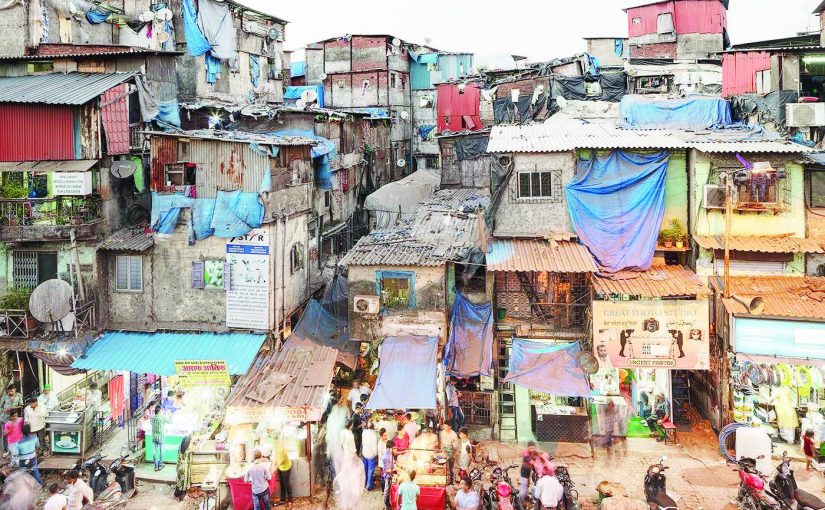

OVER CROWDED: As many as 11 members of the family of 19 became infected because they did not have even one inch of physical space, let alone one meter of social distancing. If a 100 people have to use five toilets you can imagine the degree of hygiene and risk of the rapid spread of the viral infection

By Jacob Koshy

The lockdown is intended to prevent the spread of the virus. Given the fact that 80% of migrant workers live in very small houses it has been worsening the situation. If a family of 19 stay in a small hut how can you prevent all of them from catching the infection….

Why is it important to carry on testing? Why is it necessary to pursue contact tracing and quarantine? What is the state of health-care facilities?

The story so far: It has been over three weeks since Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced the world’s biggest lockdown, in India, to fight COVID-19, the pandemic that has claimed over 1.5 lakh lives worldwide. Epidemiologists have said that the impact of the lockdown in slowing down infections would take at least three weeks to show. This is because the incubation period of the virus could extend to two weeks and any residual sources of imported infections, from before airports were sealed, would at most show up in a week.

What was the reason for a long lockdown period?

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic on March 11 but until March 13, India’s official position was that it “wasn’t a health emergency and there was no need to panic”. India, with 81 cases, was evacuating Indians from abroad and had restricted international entry through only 19 of its 37 land immigration checkposts. By March 15, it was evident to health experts and epidemiologists that the virus, SARS-CoV-2, has properties that distinguishes itself from other coronaviruses and even influenza viruses. It is highly transmittable and can evade the immune system for longer and therefore spreads quickly even without the infected being visibly sick. The virus is able to penetrate deeper into the lower airways. Therefore, to the elderly and the aged, those with pre-existing conditions such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease, it poses a heightened risk of acute pneumonia.

On March 24, Mr. Modi said: “I fold my hands to say — please stay where you are,” adding that “all leading experts say 21 days is the minimum we require to break the coronavirus transmission cycle. If we are not able to handle these 21 days, the country and your family will go back 21years and many families will be destroyed. I am saying this not as the Prime Minister but as your family member.” The night of his address, India recorded 536 cases — a six-fold jump in less than two weeks; there were 10 deaths. Government and health officials feel that a complete lockdown and cessation of travel will keep those who are infected isolated and restrict infections to contained clusters. This would avoid community transmission when it becomes impossible to trace the source of infections and quarantining is of no use. Such a situation would quickly overwhelm hospitals as seen in Italy, Spain, Iran and the United States. With among the lowest capita availability of hospital beds and health-care workers, health experts say if there are too many cases, it will be catastrophic for India.

What do the numbers reveal?

The lockdown has coincided with an increase in testing and the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) has widened the pool of people of suspected cases who need to get tested. Earlier, only those with a travel history and displaying symptoms were being tested. Now, even those who show flu-like illnesses and are in a hotspot are likely to be tested and quarantined. Since the lockdown, confirmed cases have risen 23 times to around 14,000; deaths too have risen 40 times.

Every weekly rise in cases has seen an increase by a factor of 3.7, 2.5 and 2.0, respectively, until April 16. Testing grew in those same weeks by a factor of 2.4, 2.1 and 1.1 times, respectively. A slower growth in testing thus appears to be corresponding to a slower rise in confirmed cases.

Should India test more aggressively?

Increased testing does not necessarily mean a rise in cases, and could be explained by a fall in the speed of disease transmission. However, to conclude so would be premature, caution health officials. That is because India has still tested only a limited proportion of its population. There is a pool, and we do not know how large, of asymptomatic people, that is those who have been infected but do not show symptoms, but can infect others. Testing must be increased and contacts traced so that asymptomatics are also under the radar. Only this week India has effectively unveiled a new set of strategies — the use of rapid antibody tests and the concept of pooled testing to estimate the extent of undetected infections in hotspots which are places with a large number or large increase in cases. These are useful but relatively crude measures and can still lead to several asymptomatic people going undetected, according to health officials.

Is the lockdown being followed?

While India’s lockdown has been among the harshest in the world, there have been several instances of people gathering in large numbers. In fact, the makeshift relief camps that States have set up for migrant labour, the high average density of population are all aggravating factors for the spread of clusters as is seen in Mumbai.

Finally, India’s high dependence on imported testing kits and the chemicals needed to analyse them means that testing cannot be equally ramped up across the country. The ICMR has said that it has enough testing kits “for the next eight weeks” but this does not account for the variable testing capacity of various States. The extension of the lockdown for another three weeks, until May 3, may buy time but the government needs to clarify its goals. Does it expect the number of hotspot districts of which there are 170 as of this week to come down? Is it to bring down the number of infections by a particular percentage or is it to achieve a more manageable doubling time? This refers to the time it takes for cases to double, which has increased from four days in the last week of March to seven days as of this week. The longer this stretch is, the more time hospitals will have to treat and release COVID-19 patients, refurbish and safely dedicate manpower for clinical management.

What about deaths?

Post-April 6, India has seen at least 25 deaths a day, or about 1-2% of the confirmed cases. While this proportion is in line with global trends, they are likely reflective of cases that were confirmed in one to two weeks weeks before the lockdown. On the other hand, from April 3 the recovery rate of those confirmed has increased from 70% on April 3 to 80% on April 17, which also corresponds to a dip in the death rate. In all, 80% of those infected in India are believed to be below 60.

Some States have managed to flatten the curve. What does that mean?

New cases in Kerala, on a daily count, have dropped to single digits; the number of recoveries exceeds those being hospitalised in Tamil Nadu. Telangana and Andhra Pradesh are also showing signs of a dip. These are signs that these States have been able to manage infections effectively through stringent contact tracing and curtailing asymptomatic persons from spreading infection. They also reflect the importance of having moved early to stymie the spread.

However, a region is said to have stabilised only if no fresh cases are reported for 28 days — and no State is close to that scenario yet. The rise in infections is also due to the disproportionate influence of clusters. Mumbai and Delhi show that even with high rates of testing, infections will keep rising if quarantining and contact tracing are not effective. Indore in Madhya Pradesh shows that laxity in enforcing quarantine and testing last month could have seeded several clusters that will be difficult to contain. Moreover, the demands that a total lockdown make on the economy and the extent to which it suppresses normal life can mean that a staggered relaxation of the lockdown is likely. But health officials warn that this may lead to infected people travelling to new places. India may have to continue dealing with frequent outbreaks for a while, they feel, rather than expect to decisively stamp out the disease during an extended lockdown

Courtesy: www.thehindu.com