Goa is abuzz with excitement as vintage bike and car owners, users, collectors and fans are decking […]

THE DRAMA OF CIRCUMCISION!

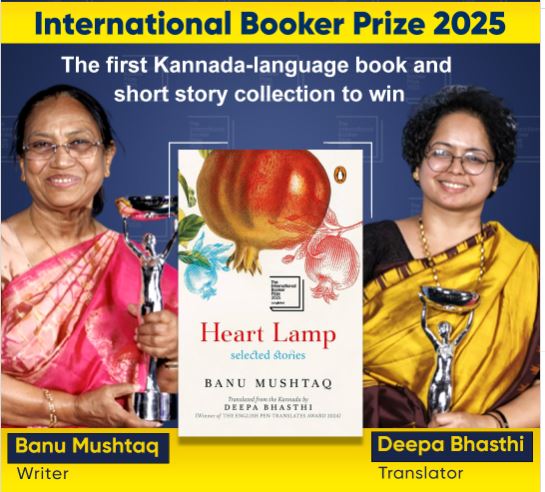

June 07- June 13, 2025, Life & Living June 6, 2025In her warm, light-hearted short story, the Kannada Booker Prize winner Banu Mushtaq focuses on the practice of circumcision in the Muslim community. While well-to-do Muslims get it done by doctors under hygienic conditions, poor Muslims are left at the mercy of traditional practices. This year’s International Booker prize-winning book “Heart Lamp, Selected Stories” is an anthology of short stories providing insight into the life of the Muslim community, including a very unamusing account of women on the Hajj pilgrimage in Mecca going on hectic shopping binges….

THERE is no end to the woes mothers face come summer vacation. All the children are at home; if they’re not in front of the TV, then they’re either up the guava tree in the front yard or on top of the compound wall, and what if one of them falls and breaks a hand? Or leg? But it’s not just that, no: it’s all the crying, the laughter, the meting out of punishments based on some arcane system of justice from another world. That’s why Razia’s headaches increased as summer vacation began. The nerves in both temples throbbed, her hot head felt like it would burst, and the veins at the back of her neck threatened to snap any time. They came, one after the other, complaining complaining, and between complaints, it was screaming and crying. And then the kind of games they played… abbabbaa… sword fighting, machine gun, bomb attacks…

‘Enough is enough,’ she thought, as she lay on the divan cot in the hall, a piece of cloth tied tightly around her head. She was in no condition to tolerate any kind of noise. The TV was still switched on, albeit at low volume. She had issued a stern warning and was hoping to finally relax and stretch out her legs when one of them screamed: ‘Doddamma! Doddamma, she is pinching me!’ Then her anger knew no bounds, and she got up, cursing them in her head.

Just as she was thinking “There are six of the damn things here already, and each brother-in-law has two-two… three-three… they have all landed on us for the holidays and my younger sisters’ children are here also, what do I do, oh god, her husband Latif Ahmad stepped inside. He became alert when he saw his wife’s condition; she had always been allergic to children. First those of migraines, and then the children rubbing masala on her discomfort with their noise, he thought, looking at them all from the corner of his eye and counting even in the middle of his helplessness. One two, three, four… eighteen children in total, all between the ages of three and twelve.

Before she could open her mouth, and just as he was scolding them (‘Eyy, all of you sit down quietly, I won’t give anything to those who make noise’), Hussain came in behind him from the farm carrying a basket of mangoes. When all the children screamed and pounced on the basket, it was Latif Ahmad’s turn to be frightened. He looked at his wife helplessly and walked towards the bathroom. Unable to tolerate the pain, Razia caught hold of one or two children within her reach and whacked them. Seeing a summer of continuous torture before her and no other way out, in the end she decided that she’d have to engineer bed rest for some of them somehow. Circumcisions, she decided. She would get khatna done.

According to her calculations, out of eighteen children, eight were girls and would be spared. Of the remaining ten, four were of even ages, at eight, six and four; those little devils would have to be spared too. Latif Ahmad agreed to her decision to get khatna done for the remaining six without a word of protest.

Theirs was a wealthy family in the district centre. Although half a dozen of Latif Ahmad’s younger brothers had government jobs and lived elsewhere, as the eldest, all family functions were conducted in Latif Ahmad’s house. Razia did not hesitate to spend money for these things. She thought of it as her duty. And the fact that two of the six eligible boys were the sons of her younger sisters also brought her joy.

Preparations began as per her instructions. Several metres of fabric was bought. Even the children began to join Doddamma in making arrangements. She cut the fabric to measure and made lungis. The girls had a lot of work, stitching sequins on the lungis and painting them, but making lungis for six boys did not require the whole roll. There was a lot of leftover cloth. When she wondered what to do with it, the solution arrived: ‘Arey, there is our cook Amina’s son Arif — also our worker’s son Farid — let us get khatna done for some other children from poor families,’ she thought, and translated the idea into action immediately.

There were five masjids in town: Jamia Masjid, Masjid-e-Noor and others. After the Friday namaz, the secretaries of all these masjids took the mics and conveyed this message: ‘Latif Ahmad Saheb has, as an offering to God, made arrangements for a mass Sunnat-e-Ibrahim next Friday after the afternoon namaz. Those interested must register their children’s names in advance.

They could have just said khatna, colloquially speaking. But since the words uttered from a stage and through a mic have to be formal, the secretaries did not, instead calling it a celebration for Prophet Ibrahim. But both mean the same thing: a collective exercise in which children look forward to an event but end up screaming loudly together.

Everything transpired just as Razia had expected. A lot of poor people came and registered the names of their children. Razia cut cloth for lungi after lungi. Only the children at home got to have sequins and zari on their lungis; the others were plain red. On her son Samad’s, there were so many sequins one couldn’t even see the colour of the cloth. Sacks of wheat and copra were brought in. Ghee made from the finest cow’s milk, almonds, raisins and dates were bought for the children at home.

The children were strangely restless, agitated; everyone else was happy; the air was festive. Friday arrived before they knew it. Once the afternoon namaz was over, Latif Ahmad quickly finished his lunch and appeared in the compound next to the masjid. A lot of people had gathered; the parents who had brought their children, as well as the children who were to get done, were all standing in line. An army of young attendance as volunteers. All were dressed in white shalwar and jubbas, with either white topis or white cloths tied on their head. Since they had taken baths for the Friday namaz, they all looked fresh and clean. Many had lined their eyes with surma and generously dabbed on scent, so the whole atmosphere was filled with pleasant smells.

Arrangements had been made for khatna inside the madrasa close by. Ibrahim, who was built like a wrestler, was the special guest that day. His biceps were prominent under a thin white mul jubha. Doing khatna was his traditional profession; he practised the barber profession the rest of the time. He was involved in necessary preparations in one corner of the expansive madrasa hall. He hurried about and placed his bronze bindige pot upside down. He’d had it brought for the ceremonies. Razia had made Amina scrub that bindige with tamarind juice two-two times to make it shine. A plate, filled with finely sieved ash, was kept on the floor in front of it.

Ibrahim inspected all the arrangements until he was satisfied. He was a very experienced hand. It was said that once he brought the knife down, the khatna would be done perfectly and heal without infection, such was the fame of his healing powers. In another corner of the madrasa hall, a group of young men were spreading out a large jam khana and smoothing away wrinkles. Ibrahim checked everything over once again and got up slowly. He took a shaving knife out from his pocket, moved it across his left palm and instructed, ‘Bring them in one by one.’

Standing next to him and looking agitated was a volunteer named Abbas, who, unable to stop himself, eventually blurted: ‘If you give me this knife, I will sterilise it in hot water and bring it back. We can add a little Dettol to disinfect it too, I think. Having noticed Abbas from the corner of his eyes, Ibrahim understood that his was a brain that had climbed the steps of a college. He looked at Abbas with the disdain reserved for vermin and mockingly asked why. ‘So that there is no chance of a septic…’ trailed off the flustered Abbas, as Ibrahim was not done mocking, and cruelly asked if he had had such an infection himself. Abbas’s friends started giggling, ki ki ki, all around. Abbas, irritated, scolded — ‘You are all so uncivilised’ and moved away. Ibrahim smiled triumphantly and called out once again: ‘All of you come one by one.’

The volunteers standing outside ordered the boys to remove their underwear. The first in line was Arif. He was a grown-up boy, around thirteen years old. Usually boys had to be circumcised money before the age of nine. But his mother Amina had not had seen age to get the procedure done. Watching him remove his shalwar and pull his shirt down, people around him laughed. A young man who struggled to control the laughter behind his lips punched Arif lightly on the back and pushed him inside.

About four-six people grabbed him and made him sit on top of the bronze bindige. He was confused. Before he knew what was happening, a pair of strong arms came from behind, went under his armpits, rested on his thighs and parted his legs. By the time he started screaming in terror, two people held his left and right arms tightly. His heart was beating loudly; he wanted to escape. But those who held him tightly were smarter and stronger than he was. They held him so tight that he could not even wiggle. He tried with all his might to free himself, failed, and screamed as if his throat was going to tear apart: ‘Let go, let me go, aiyo… Amma…Allah! Three four voices, as if they were waiting for just this, said, ‘Eyy you should not scream like that, say deen, deen. Between gasp Arif repeated, ‘Deen – deen – Allah – Allah – Amma – aiyoo…’

While all this drama was going on, Ibrahim calmly took a piece of bamboo as thin as paper and attached it to Arif’s penis, arranging it so that only the foreskin was in front of the bamboo clip. One of the men turned Arif’s face to one side and urged him, ‘Bol re, say it, boy. Say deen. Say it quickly, quickly! Deen has many meanings, belief, faith, dharma and so on, but without knowing any of them Arif tore his throat apart screaming it. Deen! Deen! His tongue dried up; sweat dripped down his back; heat rose in his body; his hands and legs went cold with fear. As if for the last time, he made a futile effort to free himself.

‘Why, boy?’ asked one of the volunteers holding his legs down. ‘Let me go, let me go, I have to pee,’ he begged them, only to be told ‘Wait for a while, you can go then. They held him tighter. At that very instant, Ibrahim brought out the razor he was holding behind his back and slid it over the part of Arif’s penis in front of the bamboo clip. The foreskin fell on the ash-filled plate in front. Blood spurted from the wound. Ibrahim took some of the ash from the plate and sprinkled it gently on the cut. The dripping blood mixed with the ash, and its flow began to reduce. Arif’s face was pale. He was soaked in sweat. Little gasps were still coming out of his mouth sporadically. Two young men lifted him, brought him unceremoniously to a corner of the hall, and laid him on the floor.

The cold plastering on the floor gave his backside some relief. But still, there was a burning pain… A few young men caught hold of another boy and ran towards Ibrahim. Abbas was coming near. He poured some water into his mouth from a cup and began to fan him. Right then another voice thundered, ‘Deen, deen!’ Even Arif was holding his stomach and writhing in pain, they brought another boy and laid him down on the mat.

‘Deen! Deen!’ different voices continued screaming. Bodies were thrashing about in pain here and there. As for Asif, even with the searing pain, his eyes were drawing shut. Sleep overtook him but went away just as suddenly as it had come. Before he knew it, he was awake. He drifted in and out a couple of times and was nearing deep sleep when someone started shaking him gently. Although he was still in pain, it was no longer unbearable, and he slowly opened his eyes. Abbas was standing before him, his face sympathetic, and asked, ‘Arif, can you walk? Look over there, your mother has come. He tried to look at her from where he lay. His mother, wrapped in a burkha that was torn here and there, with holes in many places, could neither come in front of the men nor leave her son alone in such a condition. She stood peeping a little from the other side of the door. The sight of his mother’s faded burkha gave Arif a fresh dose of energy. Abbas helped Arif up, and they walked slowly till they reached her.

Just as Arif was approaching the door, Latif Ahmad, who was sitting on a stool, placed a bag in his hands. Even though he was in a lot of pain, Arif peeped into the bag. It was full of wheat and two halves of copra. One packet of sugar, butter in another plastic packet… his tongue began to water. A boy who was about to go inside fell at the doorstep and started crying. Arif stood up straight like a hero, looked at the boy and shouted, ‘Eyy, Subhan, don’t be scared. Deen… say that. Nothing will happen.’ He had already acquired some seniority. Arif came out limping. Amina took the bag from his hand and made him sit on the veranda outside. He spread his legs out and sat carefully, ensuring that the lungi did not touch the wound. A boy standing in the line asked him loudly, ‘Lo, Arif, does it hurt?’ Careful not to show any signs of pain on his face, Arif replied, ‘No, not at all, kano, it does not hurt even a bit.

A bearded middle-aged man standing nearby heard him and said, ‘Shabash, son, here, take this, for your care, giving him a fifty-rupee note. All the boys standing in line looked at him enviously. Screams could be heard from within. ‘Deen … deen… aiyo… Allah…’ Another boy got shoved inside.

The boys kept going in one by one and coming out wearing red lungis. That was when she arrived. She was extremely thin, her eyes set deep in her face. One couldn’t see a waist on her body, yet, surprisingly, she carried a child on it. A patched-up blouse hid under a torn saree. She was dragging a six- or seven-year-old boy with her other hand. The boy was wiggling about a lot, but her grip was strong. His cries were heartbreaking. The woman tried to pull her torn saree over her head a little, and it tore some more in the process. In a voice even she could barely hear, she called, ‘Bhaiyya!’ Engrossed in talking to someone, Latif Saheb turned back to look and asked, ‘What is it, ma?’

The boy started crying louder. ‘Get Sunnat done for him too, Bhaiyya,’ she said. ‘No, no, I don’t want it,’ the boy shouted and was about to flee. The mother held his arm tightly. The veil on her head slipped. Her dried-up stomach, her protruding collarbones, hollow eyes, patched-up blouse, all these offended Latif’s eyes. He averted his gaze to the floor and scolded the boy. ‘Eyy, stand quietly. Will you not be part of deen? Until you get khatna done, you will not belong to Islam. Will you remain like that?’ The boy spat out the truth amidst sobs: ‘I have had khatna done.’

Agitated, the mother immediately said, ‘But Bhaiyya, it was not done properly, it can be done once more! Although Latif Ahmad thought something was amiss, he could not be sure. He called one of the young men standing nearby. ‘Ey, Sami, catch hold of him and see what has happened. Some mischievous boys waiting for entertainment lifted the boy up suddenly. One dragged the boy’s shorts down. The ill-fitting pair of shorts, made to someone else’s measure, slid easily. Everyone held laughter on their lips and in their eyes, and looked on with curiosity.

‘The khatna has been done properly.’ All the boys let out the laughter they had tried hard to suppress till then. One of the men bristled and said, nastíly, ‘Bring your husband too. Let’s get him circumcised and give you wheat and copra.’ There was another wave of laughter.

The moment his hand was let go, the boy pulled up his shorts hurriedly and vanished. His mother pulled the threadbare seragu over her head and walked away, dragging her feet heavily. One of the men spat out in disgust and said, “Thoo! What all kinds of people there are in the world… They will stoop to any level.’

A little while after she had gone, Latif Ahmad began to feel uneasy. When there was so much poverty and misery around, was there a need to be inhumane too? She came before his eyes again and again. ‘Che, I should not have sent her away empty-handed: He began to feel agitated. He looked around, but she had vanished just as suddenly as she had appeared.

The line kept moving forward. Red lungis kept coming out. Latif Ahmad looked at the clock impatiently. It was already five in the evening. The well-known local surgeon, Dr Prakash, had asked him to bring the children from his household to get circumcised by six. What might those children be doing now? Razia had bathed all of them that morning, and Samad, her eldest son, with extra love. She had been telling her husband for the past six years, that is, since Samad was five, ‘Let’s get the child circumcised, he has become very thin.’ She had hoped that at least after khatna he would put on some weight. But Latif Ahmad did not have the courage, and had given one or the other excuse to postpone it. The time had finally come. But he was still a little anxious.

Razia’s brothers-in-law had come for the ceremony. Her sisters had also travelled long distances to come home. The house full of guests; all the children wore new clothes; the boys getting khatna done strutted about. While all the young and old men had gathered at the masjid for the mass khatna event, most of the town’s young girls and older women had gathered at Latif Ahmad’s house.

After lunch, they made the boys in sherwani, Nehru coats and zari topis sit down in a row. Garlands long enough to touch their feet fell on their necks. They wore jasmine flowers around their wrists. Well-wishers came. They cuddled the children. Someone slipped gold rings onto their fingers; someone else gifted them gold chains. The five-hundred-, one-hundred-rupee notes they received were too numerous to count. Everyone who came performed the ritual of removing the evil eye by cracking knuckles over the children’s heads. Betel leaves, bananas, karjikaayi and other snacks were distributed. No one had the time to talk to each other. The house was filled with confusion, chaos, hurry-burry.

She was standing in front of Latif Ahmad. Tired of standing, he had got someone to bring him a chair and had sat on it to supervise the mass khatna event. Just when he was opening his mouth yawn aaaa, she came before him. She was thin, but her breasts had not dried up; an old sweater covered them. She had tied an old scarf around her head. Her face was pale. She held something in her hands, a cloth bundle pressed to her chest.

‘Bhaiyya! Get Sunnat done for this one also. Latif Ahmad looked at it. He stared at the one-month-old tender bud, wrapped in that piece of cloth, and looked up at the mother. He became anxious that the young men standing close by might surround him, and each might have something nasty to say. Without another word, he took out a hundred-rupee note from his pocket and placed him and holding Samad. The woman did not stand there a minute it in her hands. He began to feel as if it was Razia standing before longer and walked away quickly without a backward glance. He began to feel again that he should have given a little who had come before. But then… another woman…yet another… one more…they will keep coming… where is the end to this? After the last boy was circumcised and he had sent everyone home, Latif Ahmad began to feel calm. Now he had to see after the children at home.

By the time he reached his house, everyone was ready to go to the surgeon. Dr Prakash had told Latif Ahmad: ‘You all come by six o’clock. Let us give the children some local anaesthesia and the operation done without causing them any pain. If the children to sleep at night, they will wake up feeling fresh in the morning. Thus, the whole family had gathered in front of the operation theatre at Dr Prakash’s children’s hospital in the evening. The operations took place without any problems, though some children cried and fussed.

After they had been brought home, the children were made to sleep on soft mattresses under fans. There were people to wait hand and foot on them. Except for one or two children groaning in pain now and then, there were no other sounds. There was no shortage of laughter, loud chatter and festivities in the house. Every eight hours, the children were woken up, given almond paste mixed with milk and painkiller tablets, and made to lie down again. The next day most of the children had recovered. There was an abundance of good food to aid their healing. Milk, ghee, almonds, dates….. There was enough of each to eat and even throw away.

The fifth day after the mass khatna event, there was a lot of noise coming in from the front yard. Razia came down the stairs and peeped out and was surprised to see the cook Amina’s Two of the servants were shouting at him to get down. His mother was standing below the tree, by turn begging the servants and beseeching her son. After he had had his fill of the fruits, Arif climbed down leisurely. The servants caught hold of him. When they brought him to Razia, he casually took out another guava from his shirt pocket and bit into it. Razia had the servants let go and asked, surprised, ‘Has your wound healed?’

‘Hmm, yes, Chikkamma,’ he replied and parted his lungi without any sense of shame or hesitance. Razia could not believe her eyes. There was not even a bandage on his wound. The cut had healed. There was no pus or infection either. The wound had healed! Her son Samad was not even able to stretch his legs out. Even with all the antibiotics he was taking, the wound had become infected. Just that morning, when he had to be bathed, he had not been able to take a single step. They had to carry him and make him sit on a stool in the bathroom. They had used a sterilised steel cup to cover the wound so as not to get it wet and had then bathed him. He was exhausted after that. His body had been dried gently. A nurse sent by Dr Prakash had come and put a fresh bandage on the wound and given him an injection. And here was this boy, playing like a monkey on top of the tree. She could not stop herself from asking: ‘What medicine, what tablets have you been taking, Arif?’

‘I have not taken any medicines, Chikkamma. That day the ash that they put on the fresh wound, that is all…

In fact, Razia did not know how khatna was done for these poor children. After hearing that ash had been sprinkled on their wounds, she got very agitated. Worrying what might happen if one of these poor children died, she came inside. After looking over all the children sleeping upstairs, she went to her son. Samad was also sleeping. Fruits, several types of sweets, biscuit packets and dry fruits were piled high on the teapoy next to him. She peeped down to the front yard. She thought that if she could see Arif, she would call him up and give him a packet of biscuits at least. But he was nowhere to be seen. She laid a thin blanket over her son, came down and went to the kitchen to supervise the cooking.

Chicken soup had to be prepared for the circumcised children. Pulao and kurma had to be made for the guests at home. It was not even ten minutes since she had come into the kitchen when she began to get very restless. Amina was working swiftly, but even though Razia felt that the food would not be ready in time if she was not there to supervise, she still did not feel like staying. Leaving the chicken that she had been inspecting, she rushed upstairs. She had shut the door behind her to ensure Samad’s sleep was not disturbed. When she pushed the door open, a heart- stopping scream fell out of her mouth. It was as if a black screen had fallen over her eyes. When the relatives heard her scream and rushed out of their rooms, what they saw was an unconscious Razia and a blood-soaked Samad on the floor. Samad had woken up and got down from the bed to look for his mother. By the time he reached the door, he had fainted. His head had hit the wall and blood was oozing out. The raw wound from the operation had also opened up and blood was dripping from it. In the end, he had to be admitted to hospital.

On the eleventh day, the children from Latif Ahmad’s family were given a ritual bath. That was the day Samad also returned from the hospital. There was a grand function that evening in the house. The whole town had been invited; several goats were slaughtered. Grand preparations had been made for the feast. A shamiana had been set up in front of the house and on the terrace. The smell of biriyani wafted from the backyard in waves. There was a lot of festivity. Samad was still very weak. Razia had not let him out of her sight even for a second. She placed his head on her lap and was talking to everyone from the bed she was sitting on.

As she sat there, she noticed someone passing by the corner of the drawing room and called out, ‘Eyy, who is that? Come here. The passer-by heard her and came back saying, ‘It is me, Chikkamma, me.’ Razia opened her eyes wide to see – Arif! Although he was wearing a worn-out shirt with a torn collar, his face radiated health. He had already discarded the red lungi and started wearing trousers. This meant that his wounds had healed completely. She filled with tears. eyes bled to herself, ‘Khar ku Khuda ka yaar, gareeb ku parvardigaar’ – if She grum- there are people to help the rich, the poor have God.

Her gaze went to the trousers he was wearing. The threadbare trousers were torn at the knees. Seeing Razia silent and lost in her own thoughts, Arif turned to leave. When he turned, what she saw were two big holes at the bottom of his trousers and shirt. She was appalled.

‘Wait, Arif,’ she said, getting up. She opened the bureau and badam cast her eyes over Samad’s neatly folded stack of clothes. About ten-twelve pairs of clothes that he had received as presents were still unopened. She placed a pair bigger than Samad’s size in Arif’s hands and said, “Take this. Go and wear these clothes. When you come to eat, you should be dressed in these clothes, OK?’

Arif’s eyes began to twinkle. More than gratitude, his look reflected a sense of devotion. He moved a hand over the T-shirt tentatively, and Razia smiled. Samad sat up, laying his head on her shoulder. Arif kept looking at both of them and began to walk slowly towards the door, hugging the clothes Razia had given him tightly to his chest.

(`Heart Lamp, Selected Stories’ by Banu Mushtaq, translated from the original Kannada by Deepa Bhasthi –winner of the English PEN Translates Award, has been published by Penguin Books, soft cover, Rs399.)