CHRISTMAS

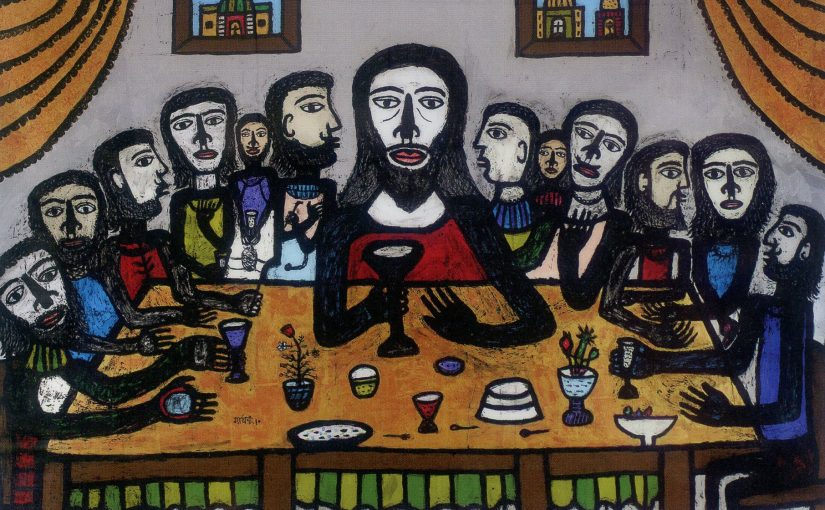

Last Supper by Mhadhavi Parekh

Fr Victor Ferrao, professor at Rachol Seminary in south Goa, laments the persistence of caste among Christians. He notes that caste and Christianity are contradictory and that Jesus Christ himself embraced everyone from fishermen to lepers and even prostitutes. Fr Ferrap welcomes the belated admission by the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of India on the discrimination against Dalits and the action plan for addressing the issue

By Fr Victor Ferrao ,

A caste masks itself in multiple forms in our society. From time immemorial, it hid under the cover of religion. Today one can discern that it has penetrated every side of our life.

We may claim to have progressed by leaps and bounds on the wings of science and technology, yet we can still find ourselves neck deep in the madness of caste. It has a way of transcending all divides in our society. Religious, political, cultural, regional and political divides merge and caste enjoys a seamless social life. It is profoundly economical. It has infiltrated our democratic structures, tainted our political ideologies, and contaminated our educational system.

Come elections, we do not caste our vote but vote our caste. It has effectively come to occupy every bit of our mindscape and landscape in our country. What passes of as nationalism today is profoundly embedded in caste. Our nationalism has no nation but caste written all over it. Caste marks our body at birth. It names and shames large sections of our people. It is a stain that refuses to leave us even at death.

It is imprinted on the innocent bodies of women. They are forced to become boundaries and gate keepers of caste purity. Caste is practised on their body. Even gods have no space outside the caste tangle. All folk deities have to be born again. Everything has to be Sanskritised. There is no salvation outside caste in our country.

Christianity in India is not free from caste. Caste has found a way to tarnish the purity of Christian love and service. Though it smears the heart of all Christian principles and ideals, it somehow remained unquestioned for a long time. It sullied our theology and corrupted our liturgy. We may have been guided by caste principles in the pursuit of inculturation and indic theologising.

But all is not lost. This Christmas, there is a glimmer of hope. The recent open admission of the Catholic Bishops Conference of India (CBCI) that Christianity in India is not immune to caste has sent several people thinking. The official document of the CBCI on the policy of Dalit empowerment in the Catholic Church in our country is indeed humbling as well as disturbing. A short statistical note, in a 44 page report, provides an insight into the manner in which caste wields itself in the power structures of the Church. But the fact that the CBCI document does not stop by stating the obvious is comforting. The CBCI has asked its 171 diocese to submit long- and short-term plans within a year to end caste discrimination against Dalit Christians.

This is indeed is a revolutionary step. It blocks the escape route that masks caste as only a Hindu practice. Christians are indeed marked by caste. Caste continues to afflict Indian Christians within their community. Hopefully, issues emanating from caste discrimination will now be addressed and justice and dignity for all will be guaranteed within the Christian fold in our country.

Christians in Goa like other Goans carry the blot of caste. Perhaps the word caste was born out of a Portuguese encounter of exclusive birth centric discriminatory practices prevailing at that time. It might be of interest to us to dissect what we have done with what the Portuguese identified and named as caste.

Scholars like Nicholas Dirks demonstrate that caste has metamorphosised over period of time. But this important analysis cannot be done here. Here, we are concerned how caste affects and afflicts us Goan Christians here and now. Caste seems to have a long memory among the Goan Christians. We Goan Christians have forgotten the gods of our ancestors but have a rather strong memory of the caste of our ancestors. The caste of our ancestors has become our caste as we seamlessly migrate into our Christian faith. Caste has come to live with Christ and none of us is disturbed by this scandal. We are deeply numbed and anaesthetised and cannot identify caste afflicting our community. Even several Catholic men and women in cassock and habit are not free from this sin of our society. A quick survey of our marriage patterns tells us that we do not share our women beyond caste boundaries. Our confraternities, some major feasts ad holy week ceremonies in several of our parishes are distinctly marked by caste. Caste has even impregnated the way we speak our mother tongue.

In several places caste is territorialised and settlements of people remain physically bound to humiliation attached to places that they live in. Caste does not just have histories. It is a geography. It marks our spaces of purity and pollution. The spatial underpinnings of caste were more visible in the past. Certain places became sources of endowment of privilege within the Church and were reserved for higher castes. Even death failed to be a leveller. Graves were also hierarchically ordered in the cemetery. Thanks to reforms within the Church, we no longer have caste reservations among the dead. Caste-geographies and biologies still abound everywhere in Goa though they are significantly under the attack of urbanisation.

Thus, for instance, several villages in Salcete appear to be distributed exclusively among the top two castes for domination and exploitation. Curtorim, Loutolim, Raia, Margao, Benaullim and Verna exhibit an exclusive presence of the Brahmins, while other villages like Cuncolim, Velim, Chinchinim, the coastal villages of from Cavellosim to Causaullim are inhabited by the Chardos among the Catholics. Same may be found in other parts of Goa. Besides, we can identify a long territorial strip, beginning from Cortalim, Quellosim, Rassoi, Rachol, Arlem, Fatorda, going up to San Jose Areal, Paroda, Quepem and Ambaulim that is exclusively assigned to the Catholic ST community. It is interesting to note that these mull nivasi community mostly do not own its land but are living on the land owned exclusively by the high castes. That is, the issue of land ownership that seemingly flows along with caste privilege cannot be ignored and have to be critically studied with deep attention and compassion.

Caste stays clothed in Christianity as well as it remains external to it and victimises the Christian community in Goa. The way the Christian community is portrayed in narratives of history is also an indication of the purity pollution principle of caste guiding our historiography. These narratives deny agency to Goan Catholics and picture them as objects of forced conversion. This means Goan Catholics as ‘forced into Christianity’ become impure Christians.

Thus, Catholics are framed within the purity pollution narrative of a caste-laden historiography in the hands of several noted historians of Goa. Along with the denial of agency of the Catholics, there is total erasure of Gavkarias, in the narratives of conversions. Most colonial history is written in post-colonial times from a nationalist position. These nationalist narratives are rooted in the paradigm Goa indica and are based on an absent nation. The absent Indian nation becomes present in these frameworks and guides the historiography. That is why we see local uprisings like the Cuncolim revolt gets represented as a national revolt. Other local nuances of the plural pasts like the rivalry for hegemony between Vaisnavas and Saivas get silenced in several caste directed narratives of the colonial past.

One can trace that caste virus afflicts the Catholics doubly. Caste killsboth from inside and outside. No Catholic chief minister has completed his full term. The caste angle might, in this musical chair politics, open other widows on contemporary history. The de-konakanising of Romi Konkani in favour of a nargrised version of Konkani, the continuous fight for primary education in Konkani and Marathi alone also has caste written all over it. Thus, caste has a way of staying within as well as transcending and oppressing Christians in Goa.

This Christmas, we in Goa cannot close our eyes to the existence of caste within Christianity. Indeed, we cannot serve both Christ and Caste. It is matter of profound faith and commitment. The CBCI has given us the leadership. The demon of caste has to be exorcised. This expulsion of caste won’t be easy. It will require us to embrace the cross. Christ without his cross is like salt without its saltiness. We cannot be genuinely Christians without walking the way of the cross. Admission of the existence of caste is discomforting and painful enough. Its eradication will become even more excruciating. But just like the cross is not without the victory of resurrection, so also the death of caste will bring about freedom and dignity for all in the Church. The death of caste will bring about the resurrection of the body. Caste, being profoundly a bodily practice, will truly liberate all, particularly who suffer physical shame, humiliation and indignity. Christmas is a time to understand the mystery of incarnation. It is time to feel in our bones the pain that is felt in flesh by the outcasts. Unless we are able to see Christ in the outcast, we cannot experience Christmas. Hence, it is a challenge to let Christmas happen to us. We have the imperative to let Christmas happen to the Church and through it to everyone in our society.

This happening of Christmas is like light. Darkness is simultaneously expelled by the coming of light. So too the coming of Christ expels the darkness of caste from our society. Christmas has to lead to the death of caste from all aspects of Christian life. Being freed from caste from within, Catholics will truly become light, salt and yeast that will free our society from its slavery to caste.

Freeing ourselves from the slavery of caste demands that we overcome our dependence on caste. If caste is our master then Christ cannot become our Lord. As we surrender ourselves to the mastery of caste over us, we replicate it in several ways in our society. Because we have become slaves of the principle of caste, we end up reproducing master-slave relations of Hegel both within and beyond the Church. This Christmas, we have to choose who will be our master. We cannot serve both Christ and Caste. We have to choose one of them. This choice is not a clear alternative between an ‘either/or’ binary preference. Caste never really comes naked. It always comes clothed. It can come in the clothes of Christianity. The open admission of the CBCI about the existence of caste in the Church is that it is already dressed in Christian robes. Caste is already dressed in Christian robes in Goa. It will not easy to derobe caste from Goan Christianity. But derobe we must.

We follow the self emptying Christ. The Christmas crib is a symbol of this self emptying of Jesus. Therefore, the derobing of the caste that is hiding within Christianity will bring us into the embrace of Christ and through him we shall be enabled to stay in the embrace of every other human person. Hence, we have to abandon the embrace of caste that masks as embrace of Christ. Saying no to caste will lead us to saying yes to Christ and his people. Saying yes to Christ will let Christmas happen to us. Thus, being redeemed from caste, we can fully enjoy the freedom and dignity of being sons and daughters of God.

This self liberation of the Catholics in Goa can usher destruction of all caste afflictions from without. Such a scenario will debilitate caste from our society. Indeed it will castrate caste and check its explosive reproduction in our society at large.