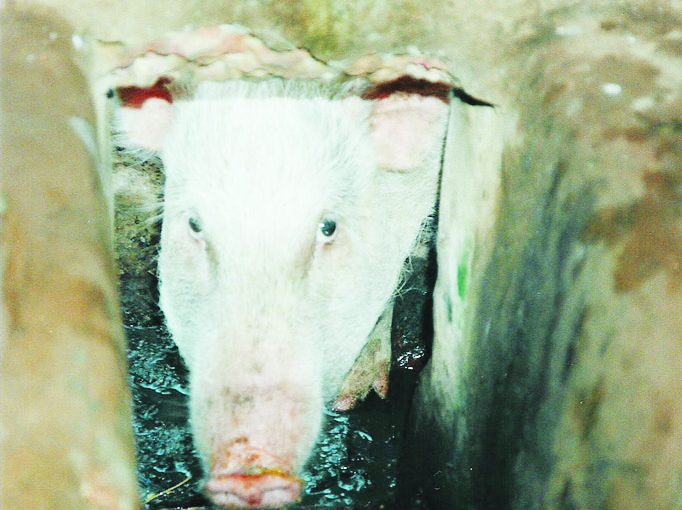

FAILURE: In spite of introducing a thousand schemes Narendra Modi has not been able to make them work, as dramatised by the accumulating garbage on Goa’s roads and the failure to eliminate open defecation in fields and streams etc. Open defecation is worse than even the old pig-toilets (in pic above) which at least did not result in the pollution of water bodies

COMPLIED BY GO STAFF

Ruchir Sharma, Morgan Stanley head and author of the new book, ‘Democracy’, says the Central government today does not know how many schemes there are…

VANDITA MISHRA: In the last chapter of your book, you say that anti-incumbency is a heartening phenomenon because it doesn’t allow anybody in power to get too comfortable. Secondly, throughout the book one gets the sense that you are looking for that grand reformer, but in the end you say that there are no grand reformers, and that hope lies in smaller changes in states, rather than at the Centre. Could you place these two conclusions in the context of the situation we are in now, in what could be India’s first national security election?

Will this be the first national security election? I am not sure because even the 1999 election was fought in the backdrop of the Kargil war, and you can argue how much that influenced it.

It is generally believed that whichever party or government is in power tends to benefit when the nation feels it is under siege. But even assuming that the BJP benefits a lot from it, assuming that their voteshare goes up a bit… No national party in India has ever got more than 50% of the votes, going back to the first election, including the Congress, given that there was one national party in all those decades. Even in this election, at best, the BJP’s voteshare will go up to maybe 35-36% from 31% — assuming that there is a surge in its favour because of this nationalist kind of movement. The BJP recognises that even during the entire movement, as we have seen in the past few weeks, the headlines are the same, the small changes … They have given up seats in Bihar, they have given up seats in Maharashtra, to accommodate alliance partners. So, for me, that’s the journey as far as India is concerned. This is still a continent like the European Union, it is not a country. There is no one narrative. So even though to us it appears that national security is the narrative, I don’t know how much of that storyline carries into the hinterland.

VANDITA MISHRA: For the bulk of the book you talk about anti-incumbency as a symptom of the ‘broken State’, but towards the end you actually hold it up as the most heartening feature of the Indian democracy.

A year ago, there was so much talk in India that we were heading towards a one-party hegemony. That the BJP had the entire organisational strength, the muscle power, the money power, and so it seemed as if there was nothing that could beat the party. That’s what the conventional wisdom was a year ago. Since then, the election results (in Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, and Chhattisgarh), and the fact that so many coalitions have come together in the states, are things that have happened despite the odds.

In this country, whosoever is in power, the entire business community fawns over that party, the entire money power seems to be with that party, despite these very obvious advantages, the underdog, with much less money, and a weaker organisation, is able to win. The conversation in Delhi is as if the business people are able to buy out whichever politician is in power, they are able to manipulate stuff. Despite that, the fact that the voter at the end of the day is able to toss out the incumbent… that is heartening.

VANDITA MISHRA: The other conclusion, which is less heartening, is your giving up on the search for the grand reformer. You talk in this context about Atal Bihari Vajpayee, Chandrababu Naidu and others. You speak about the time when you were travelling with Naidu in his hi-tech van. In his van, he is reformer. When he goes up to the roof to address the people, he is a populist. By the end of the book, you give up on the idea.

I grew up in India in the 1980s and ’90s, with a sort of naive feeling as a kid that we have got political freedom so early, then why don’t we get economic freedom? That is the basic question that would haunt me. I grew up in the era where everyone celebrated Margaret Thatcher (former UK PM), Ronald Reagan (former US president) and others. I remember having my first extensive meeting with Sonia Gandhi and Rahul Gandhi in 2002. I was 28 then. I had the hope that I could go and speak to Sonia Gandhi and tell her what the world is doing, the reforms that are taking place. I thought she was relatively new in Indian politics and that she would understand. After an hour, I walked out crestfallen. I felt I was on a completely different wavelength.

In 2004, Naidu lost. I quote in the book what he told us after he won the election in 1999 — “This is a message to the world. People are sceptical that reforms don’t take place anywhere. But, in India, free market economy can actually work.” There was a moment of hope. But then onwards, the realisation kept on sinking in that in India may be this is just not going to work.

When Narendra Modi got elected in 2014, I remember writing for The Wall Street Journal, which I look back with some embarrassment, that this is India’s Reagan moment. They loved it in the West. My idea was that because he was talking of ‘minimum government, maximum governance’, he would go down that path. At the time, many were fed up with the UPA government’s welfare schemes, which were being rolled out one after the other, with no focus on economic reforms. I was hopeful that Modi would actually do it (reform).

The biggest reform was demonetisation, which for me is the sort of policy that only a communist nation makes. I was very upset with what happened. Now, at the end of Modi’s term, it’s back to one scheme after another.

VANDITA MISHRA: So what do you think went wrong? You were very impressed with the economic reform Modi had undertaken in Gujarat.

I misunderstood it. It is very different to run a state and a country. At the state level, you can still talk to people and fix things. It’s a project management kind of approach. You can put the right people in the right enterprises. At the national level, it is very difficult to do that. At the national level you have to devolve power; give as much power as possible to the states.

VANDITA MISHRA: Why do you not like Rahul Gandhi? In the book, you write about a two-hour meet with him, where he speaks for one hour 59 minutes.

Saying ‘I don’t like him’ is a strong statement. I talk about a 2007 meeting in Moradabad. We were a contingent of 20 people. We got a one hour, 59 minute speech on caste politics in UP. I found it very disorienting. In 2010, when we met him in Bihar… After keeping the crowd waiting for four hours, he didn’t even acknowledge us properly. Back then, I think, he felt that the 2009 victory was all about him. When we had subsequent interactions with him in 2012, he was still talking to us, rather than engaging with us. One of my favourite anecdotes is from 2012. We had a senior journalist from The Financial Times who asked him a question. He snapped back at her, saying how long have you been in India, how much do you understand India? She replied in Hindi that she had been here long enough, and even met his grandmother (Indira Gandhi) in Allahabad. She knew India very well. I did begin to see some easing up just before the 2014 general elections — he himself said that the 2014 election was the biggest learning for him. So there has possibly been a change in him in the last few years. I haven’t had any extensive interaction with him since then.

VANDITA MISHRA: Priyanka Gandhi, on the other hand, seems to have made a wonderful first impression on you.

Yes, when we saw her in 2004 in Amethi and Rae Bareli, the view then was that she is the one. That time there was still speculation about whether she will join politics. She made a real impression on the group in terms of her campaigning skills. Today, it is a different India. I don’t know what difference she can make. Back then, it felt very different, and we were contrasting her with Rahul all the time. At the time, she could speak much better Hindi (than him), could connect with the people better. Now, we have to see it in terms of how Rahul does. He has changed his campaigning style. He has adopted the same Modi kind of shout-and-call, which is basically to say something and then wait for the crowd to respond.

SANDEEP SINGH: You spoke about the government’s statist control. Can you elaborate?

The Central government today actually does not know how many schemes there are. I am told that at last count there were more than a 1,000 schemes — Central and Central government-assisted schemes. Even when it comes to schemes that the BJP and Modi criticised when they were in Opposition, like MGNREGA… Today, the allocation for those are up substantially.

Also, about privatisation. Even in the Vajpayee government we saw some privatisation. Today, I think privatisation in this country is a dead issue.

To me the biggest sign of statist control in India is the fact that no businessperson will speak out against the government. In the US, if the business people do not like Donald Trump, they make it very apparent. Every CEO will tell you whether he or she is a Democrat or a Republican. In India, the fear of politicians is incredible. When you ask industrialists off the record why don’t you tell the Prime Minister that this should be done, the response often is ‘Marna hai kya (Do I want to die)?’. To me these are signs of very statist stuff… If you say anything against it (the government), the amount of opposition to that, the fear that they can come down on you like a ton of bricks, is very dominant today. (When Modi was in Gujarat) I would hear that business people could actually approach him and get stuff done. I am not sure if that is happening today. I don’t know if it is that one comment of ‘suit-boot ki sarkar’ (that has led to this), but I don’t think the businessperson today feels that heard, as compared to what it was in Gujarat.

HARISH DAMODARAN: Vajpayee headed a coalition government and introduced big bang reforms. But you are saying that Modi hasn’t done that, despite heading a majority government. Why is that?

As I document in the book, there are two things. One, there is no relationship in this country between coalition governments and reforms, and between coalition governments and growth. Indira Gandhi probably ran the most strong and stable government and was arguably the most statist in India’s history.

Two, I think, context matters a lot. In 2011-12, when we got big bang reforms, India’s growth rate had really slipped a lot. In India, I find, the best reforms only take place when the government has its back to the wall, for instance in 1991-92. I think one of the biggest mistakes that this government made, and I think it happened more out of the incompetence of the Stats Department, was to accept the GDP data revisions in February 2015. It was early in their term and the GDP data revisions to me then looked totally ridiculous. By accepting it they began to think that the economy is doing a lot better than it was. Since then the narrative has been about how things are fine, without quite accepting what the reality is. To me it was one of the biggest mistakes. I think they are paying the price for it even today.

PRANAV MUKUL: During the 2014 election campaign, corruption was a big issue. Do you think this government has succeeded in living up to its promises? And, will it be an issue in the upcoming polls as well?

I think in India corruption is always an election issue. What I have documented is that we have seen a rise of some ‘better billionaires’ in India. The ratio of good and bad billionaires has changed a bit — in favour of good billionaires. A lot of this has happened because the commodity boom went bust, the real estate sector went bust. Those are the sectors where a lot of the bad billionaires come from, compared to sectors such as technology. This has happened independently of the government.

At the top level, there is still a perception that corruption may have come down, but on the ground people will tell you that they don’t feel the difference. So that is a reason that will continue to stoke some resentment and anti-incumbency.

KRISHN KAUSHIK: In your private conversations with industrialists, what are they saying about the present government?

There is generally a frustration that they wanted more. And, there is a fear factor which they don’t like. So even if they are forced to say something in public, in private things have an effect on them in some way. There is certainly a dissonance that they have to live with.

MANOJ C G : Do you think the Congress and Rahul Gandhi are moving more and more towards the Left of Centre?

I always discount what people say when they are out of power. Left of Centre, Right of Centre, I don’t know, but in India everyone seems to be an incremental reformer when they come to power. In India, if you have to look at reforms, look at it state by state. That is where the real India story of reform is coming through. In the US, the number of (Indian) chief ministers who land up, trying to sell their states as an investment destination… That is a big change.

VANDITA MISHRA: Has the gap between the city and the village shrunk in the past 25 years because of technology and migration?

Undoubtedly. As far as voting is concerned, caste tends to dominate. Yes, things have shrunk at some level. But caste is a reality and that reality hasn’t changed in all these years of me covering elections.

VANDITA MISHRA: There is an interesting statistic that you mention in the book. You say that in 1988 there was no chief minister who was single, but by 2016 there were seven of them.

Everybody then was a family-based leader, and that was very much in sync with the Indian culture… By last year, we found that eight chief ministers were single or unattached, and the pioneer of this trend was possibly Jayalalithaa. Then there was Mayawati. There are different reasons for why this trend has come into play.

VANDITA MISHRA: Is this the Indian voter making a statement against dynasty?

It is. But I still feel that dynasty dominates in this country. There are three reasons for it. One is that there are leaders like Modi, (Yogi) Adityanath (UP CM), the RSS background people… These people are trying to make a point that we are single and so we cannot be corrupt. Then, there are leaders such as Mayawati who haven’t made a statement about it. For them it was about the circumstances that they lived through, which had to do with a very patriarchal society, where they felt that they were fighting against a cabal of people. Also, politics is a 24/7 business. The distinction between personal and private is not there. It is unthinkable in America for you to have a meeting with a leader in their bedroom.

VANDITA MISHRA: The one strand you suggest that will play a major role in 2019, is alliance. PM Modi has referred to the Opposition’s alliance as ‘Mahamilavat’.

In 2014, when Modi won the election, at the peak of his wave, he got 31% of the national vote. But the ratio between the number of seats he won and the number of votes he got was the highest in India’s history — a 9 to 1 ratio. This was because the Opposition was so fragmented. Had the Opposition been a bit more united then, even at the peak of the Modi wave, he would not have got a majority. I think this time they have understood the game. The BJP is, therefore, sacrificing seats in many states to get its coalition politics correct.

SANDEEP SINGH: How has the BJP government performed on the economic front? Will it impact polls?

Development is, at best, one of the six factors that may matter. There’s one telling statistic I quote in the book — there have been 27 instances in India’s economic history when a state government has recorded a growth rate of 8% or more over its five-year term. In 50% of the instances, the state government has lost the elections. So development is, at best, a marginal issue in elections, and to win an election in India based solely on development is extremely difficult.

RAVISH TIWARI: In your journey, what changes did you observe among those at the bottom of the pyramid?

We noticed small changes. The most transformed state, which I document as well, has been Bihar. In February 2005, we went for our first election trip to Bihar. We noticed small things. At election rallies hardly anybody wore any footwear. By the time we went for election rallies in Bihar in 2010, people were wearing slippers. In the 2014 rallies, people were wearing shoes with open soles, and now they are wearing shoes with closed soles. Also, the clothing. Even now in Bihar you see people not wearing woollen clothes because it is expensive. They wear multiple layers of clothing.

The other change that one sees is that there are many more women in voting queues now.

Courtesy: Indian Express